Volume 13, Issue 1 Fall 2017

Contents of KB Journal Volume 13, Issue 1 Fall 2017

- 36249 reads

Kenneth Burke's FBI Files

David Blakesley and Todd Deam

Todd Deam requested Burke's FBI Files in February, 1999. The Justice Department responded within several weeks to say that the files would be made available in "due time." Due time turned out to be only 45 days, in part because the files had been requested previously and thus didn't need to be censored again.

The packet contains twenty pages in all, some of which are inserts of an FBI form indicating that one or more pages is not being released because of exemptions specified in the Freedom of Information Privacy Act. Because of their location in the entire file, the missing pages appear to be from the mid-1950s, but that conclusion is only speculation. You can download the entire FBI file without annotations here. Otherwise, you can review each page and a transcription below.—DB

- View or download this single page in PDF format

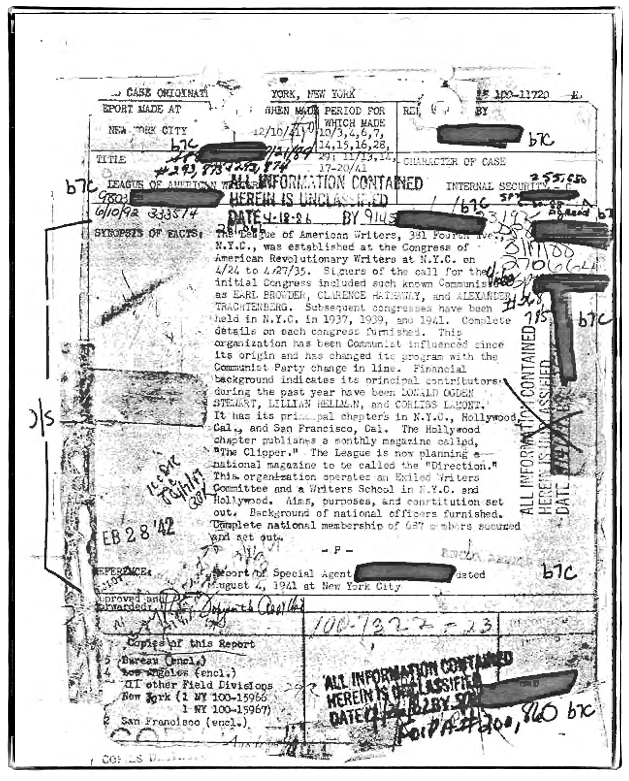

Page 2

Perhaps the first thing that strikes the attention is the degree to which the documents have been censored. In many cases, items no longer readable will likely contain names of people involved in preparing the report or who may still be living and thus subject to having their privacy protected.

This first document is one of nine to treat the four League of American Writers' (LAW) Congresses. Burke is known to have participated in the first three (1935, 1937, and 1939).

At the first LAW Congress in 1935, he presented the much-discussed speech, "Revolutionary Symbolism in America." (See Simons and Melia, The Legacy of Kenneth Burke, Madison: U of Wisconsin P, 1989, for a copy of the speech and reactions.)

This first page of the report provides an overview of the LAW and identifies the content of the report, which appears to be a typical "brief" on the organization's activities. Seven lines from the bottom, the magazine Direction is mentioned.

- View or download this single page in PDF format

- View or download the transcribed version of this page in PDF format.

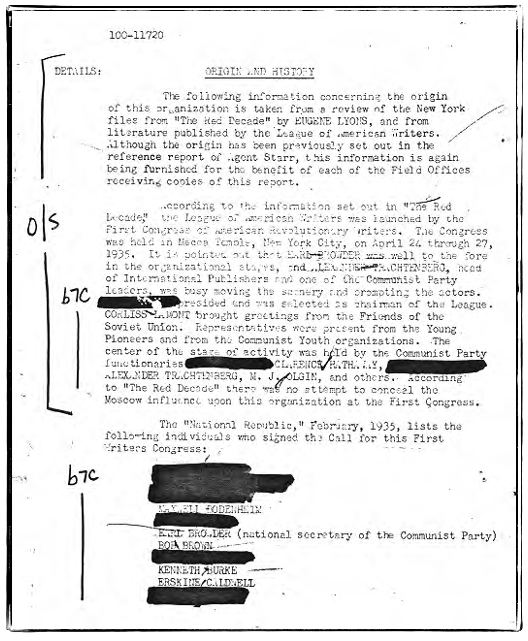

Page 3

Burke published "Literature as Equipment for Living" in Direction in 1938, as well as a series of essays in 1941-42 on the emergent war: "Americanism." Direction 4 (February 1941): 2, 3; "Where Are We Now?" Direction 4 (December 1941): 3-5. "When 'Now' Becomes 'Then."' Direction 5 (February-March 1942): 5. "Government in the Making." Direction 5 (December 1942): 3-4.

This next document notes that much of the history of the LAW used to construct this brief comes from Eugene Lyons's The Red Decade: The Classic Work on Communism in America During the Thirties. New Rochelle, N.Y., Arlington House, 1991. See also Frank A. Warren's Liberals and Communism: The 'Red Decade' Revisited, 1966, rpt. 1993, NY: Columbia UP.

Burke's name appears right above Erskine Caldwell's.

- View or download this single page in PDF format

- View or download the transcribed version of this page in PDF format.

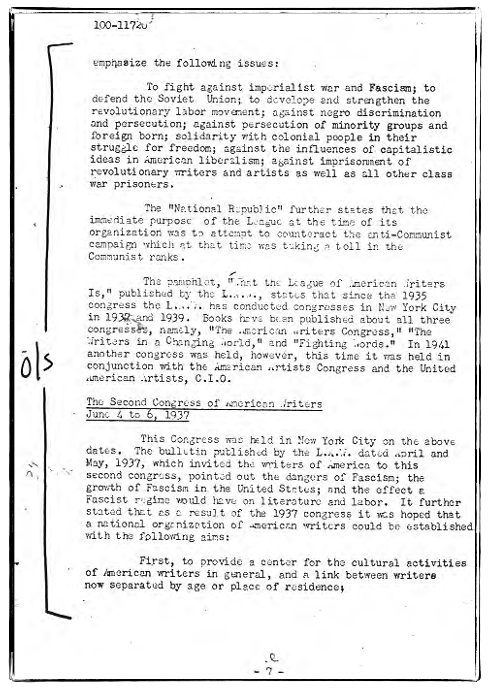

Page 4

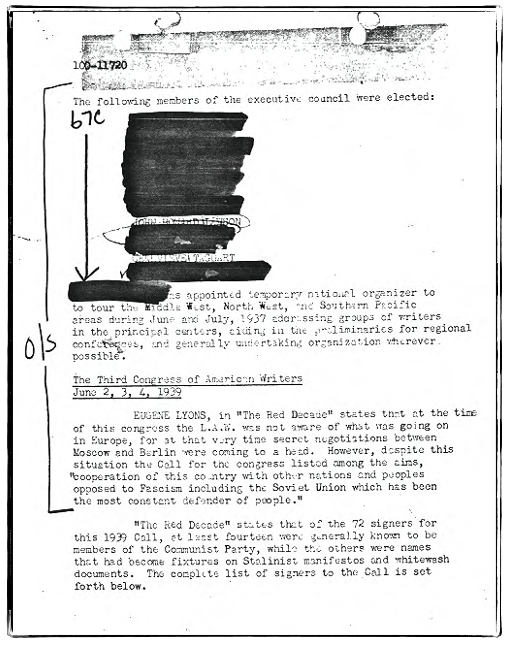

This page concludes the discussion of the first LAW Congress, then begins the narrative of the second one, held in NYC from June 4-6, 1937. Burke presented the speech, "The Relation between Literature and Science," which is republished in The Writer in a Changing World, ed. Henry Hart, NY: Equinox Cooperative Press, 1937, 158-171.

The LAW aimed in particular to fight the growing presence of fascist thinking in America and continued to ally itself with the Soviet Union, whose policies of repression under the Stalinist regime were rumored but as yet unsubstantiated in the U.S.

It should also be noted that the aims of the LAW as published in the brochure preceding the Second Congress were not as specifically supportive of the Soviet Union as were those accompanying the First Congress. The aims in 1937 focus more on role of the writer as a cultural watchdog, a healthy culture being perceived as the best defense against fascism.

- View or download this single page in PDF format

- View or download the transcribed version of this page in PDF format.

Page 5

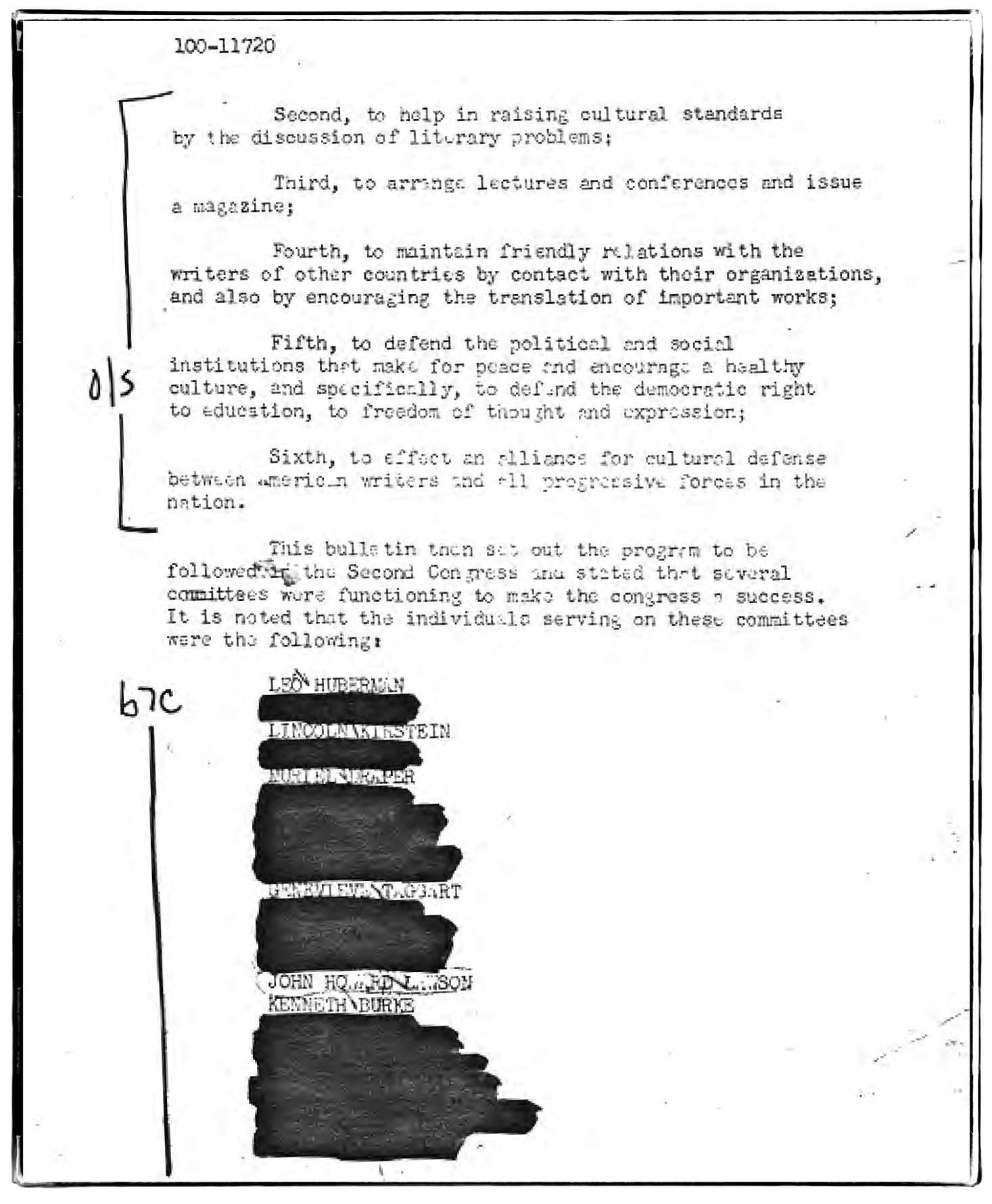

By this Second Congress, the aims of the LAW had become more focused on advancing the role of the writer as cultural watchdog. The reasoning was that, as stated in the bulletin announcing the meeting, a healthy culture was both the product of freedom of thought and expression, as well as the means of defending "the political and social institutions that make for peace," and by implication, of forestalling fascism's spread to the United States.

There's is no mention here of the Soviet Union or Stalinism, as there was in the announcement for the First Congress. The LAW had begun to back off its support of Stalin amid widespread rumors of his repressive tactics. In hindsight, of course, we now know that these rumors turned out to be true.

Burke is identified on this page as one of the individuals serving on an organizing committee "functioning to make the congress a success."

- View or download this single page in PDF format

- View or download the transcribed version of this page in PDF format.

Page 6

The presence of fascistic thinking in America was of great concern to Burke, as was evidenced in his famous "The Rhetoric of Hitler's 'Battle,'" which was delivered at the Third Congress in June, 1939. The speech was a scaled back version of the essay Burke had already had accepted by The Southern Review and that would appear a month later in July, 1939. This essay also appears in The Philosophy of Literary Form, 1941, rpt. Berkeley: U of California P, 1973.

In "The Rhetoric of Hitler's 'Battle,'" Burke describes his purpose as follows: "let us try also to discover what kind of 'medicine' this medicine-man [Hitler] has concocted, that we may know, with greater accuracy, exactly what to guard against, if we are to forestall the concocting of similar medicine in America" (PLF 191).

- View or download this single page in PDF format

- View or download the transcribed version of this page in PDF format.

Page 7

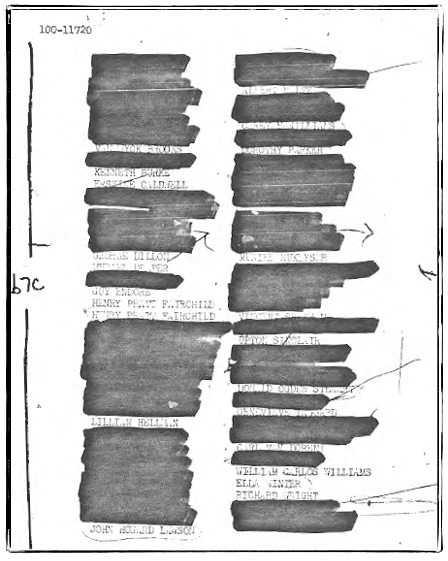

This page includes more names of people associated with the LAW. Burke is listed again, as are some of the following notable figures: Van Wyck Brooks (whose The Flowering of New England, 1815-1865 won the Pulitzer Prize for history in 1937); Erskine Caldwell (novelist; Tobacco Road, 1932); Lillian Hellman (dramatist; The Children's Hour, 1934); Muriel Rukeyser (poet; a key figure in the development of feminst poetry in the thirties), Upton Sinclair (The Jungle, 1906; Dragon's Teeth,1942); William Carlos Williams (poet, and Burke's longtime friend); and 29-year-old Richard Wright (Native Son, 1940; Black Boy, 1945).

- View or download this single page in PDF format

- View or download the transcribed version of this page in PDF format.

Page 8

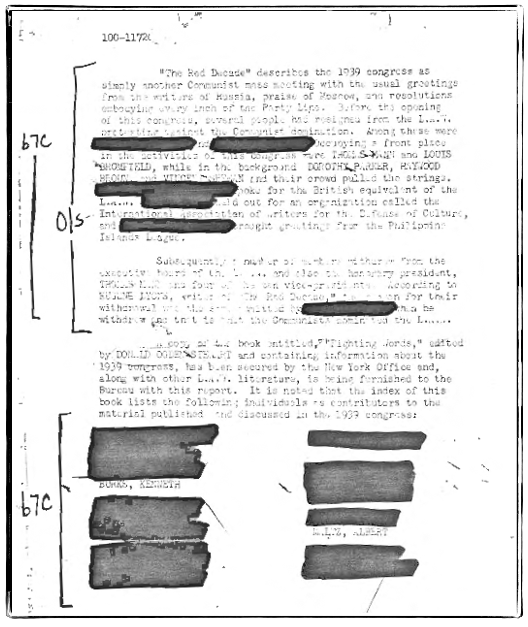

The tone expressed in this description of the 1939 Congress is one of optimism that various writers were withdrawing because the "Communists dominated the L.A.W." It is unlikely that Burke, whose name is still included at the bottom of the page as a "contributor to the material published and discussed in the 1939 congress" would have been one of those who abandoned the "cause" at this stage, having said in later interviews that he was not entirely persuaded to the truth about Stalin until well after World War II.

Thomas Mann, one of the key figures at this Congress, was greatly admired by Burke, who was the first person to translate Mann's Death in Venice into English. Mann had won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1929.

- View or download this single page in PDF format

- View or download the transcribed version of this page in PDF format.

Page 9

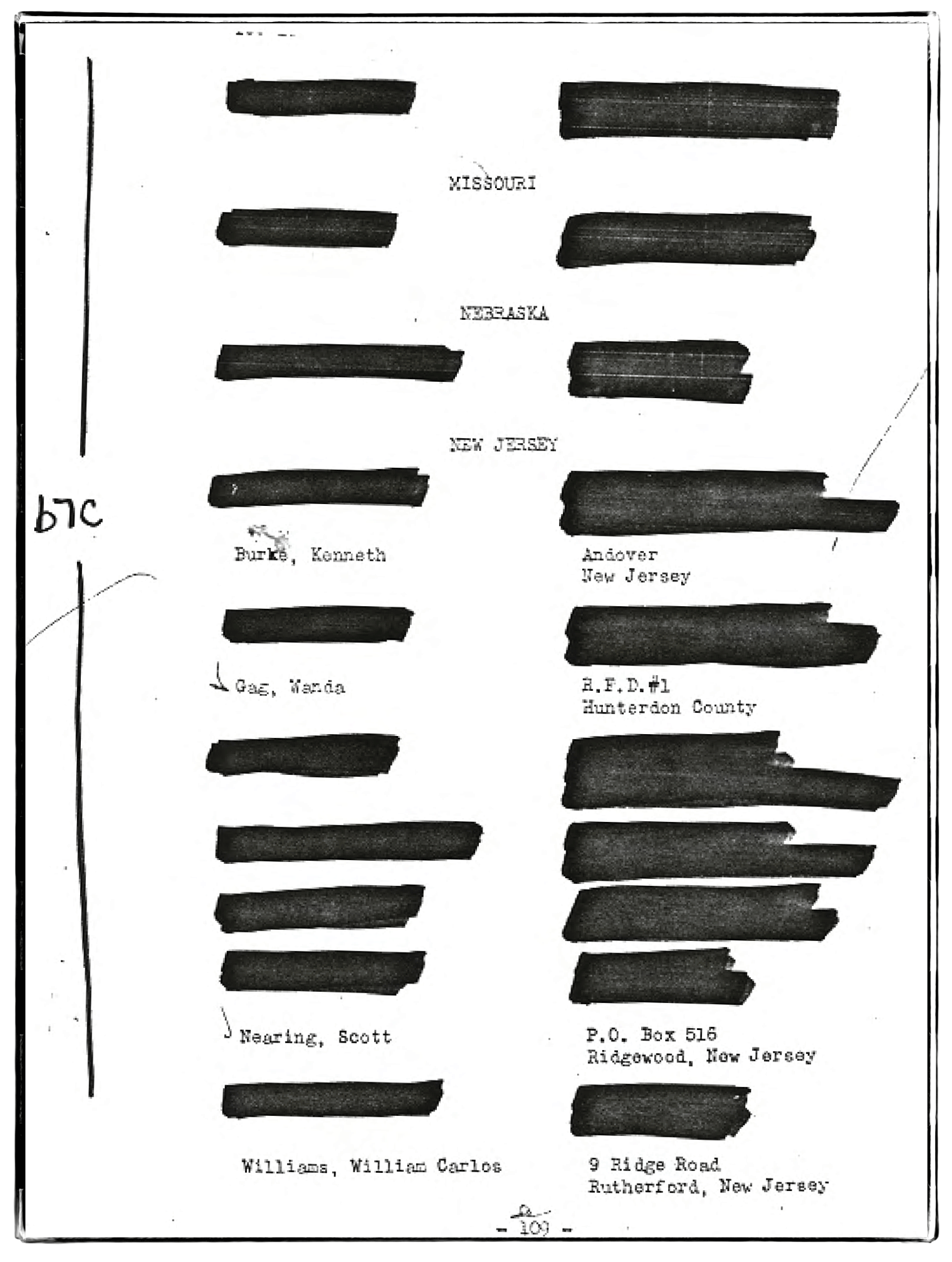

The next several pages of Burke's file include the "National Membership" of the League of American Writers for "the information of the other Field Divisions." The FBI apparently desired to continute to track the activities of those listed. It's difficult to discern the reasons why so many names have been blacked out, while others remain untouched. Little information on John D. Barry could be found, though there was a San Francisco architect and author who died in 1942 and who may be the same person listed here.

- View or download this single page in PDF format

- View or download the transcribed version of this page in PDF format.

Page 10

Burke's name appears on this page, along with his friend's, William Carlos Williams. Williams and Burke corresponded for over forty years. Their mutual influence has been discussed in such works as Brian Bremen's William Carlos Williams and the Diagnostics of Culture (1993), James East's, One Along Side the Other: The Collected Letters of William Carlos Williams and Kenneth Burke (Ph.D. Diss. U North Carolina, Greensboro, 1994), and in David Blakesley's "William Carlos Williams's Influence on Kenneth Burke," which is published on this website.

Some of you may not know that Williams performed surgery on Burke 1945 to remove a "protuberance" from his mouth. About the incident, Burke writes, "But I was disgusted when you started talking down your next book, while I had such a face full of blood and gauze that I could not defend you against yourself. What bad advertising!" (Dec. 15, 1945; Beineke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University). Williams, of course, was quite pleased to be able to have all the final words on that day.

- View or download this single page in PDF format

- View or download the transcribed version of this page in PDF format.

Page 11

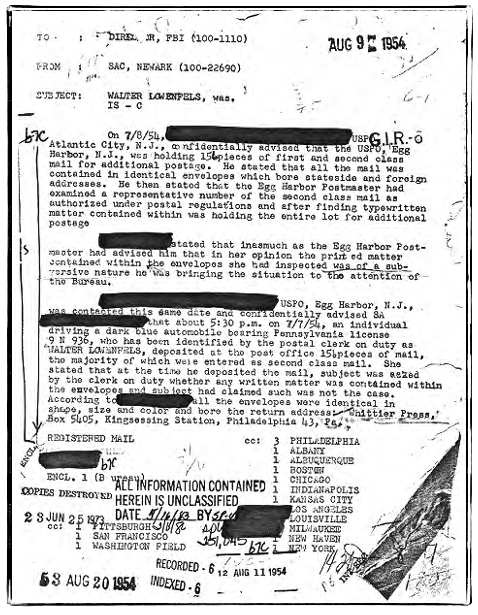

The subject of the next three documents in the files is Walter Lowenfels, whose shipment of 156 "pieces of mail" was seized by the Egg Harbor, NJ, Postmaster because of her determination that "the printed matter contained within the envelopes she had inspected was of a subversive nature." Burke, was one of the addressees.

Walter Lowenfels (1897-1976) was an activist poet and prominent editor throughout his career. According to the dustjacket on his collection of poetry, Reality Prime (1998), he was "among the principal figures in 'the revolution of the word,' the movement to modernize American writing in the early years of this century. He broke major ground as a surrealist and as a politcal poet. Closely identified with Henry Miller and Anais Nin, he was a key figure in the Paris avant-garde during the 1920s and 1930s. After Lowenfels' return to the United States, he was jailed as a Communist. He was a familiar, radical presence in non-academic poetry."

- View or download this single page in PDF format

- View or download the transcribed version of this page in PDF format.

Page 12

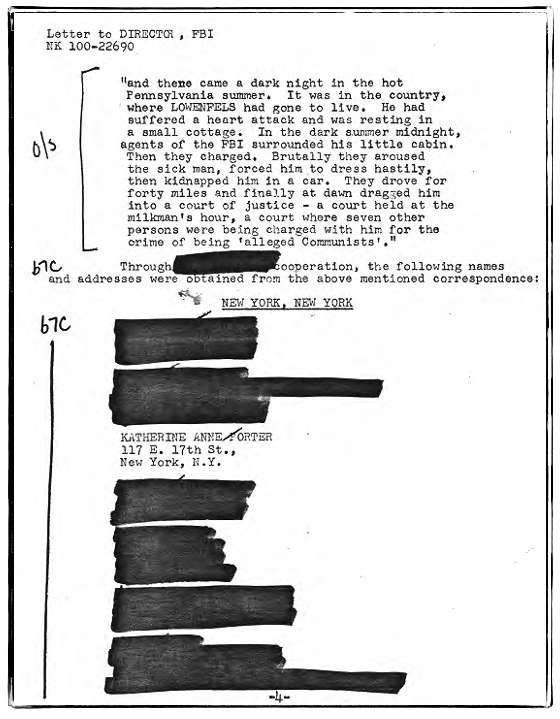

The opening quotation on this page describes Lowenfels's arrest by agents of the FBI. It is uncertain whether it is an account of the event that has been quoted from the material within the mailing (and perhaps written by Lowenfels himself).

Lowenfels was editor of the Pennsylvania edition of The Daily Worker, which is likely the newsletter deemed subversive and seized. The oldest of "The Philadelphia Nine," Lowenfels was arrested and prosecuted under the Smith Act in 1953. The Smith Act, otherwise known as The Sedition Act, was used by the Federal government to prosecute Communists during the late forties and early fifties for "inciting the overthrow of the government."

Katherine Anne Porter is the famous short story writer, feminist, and socialist who later in life argued for separating art and politics.

- View or download this single page in PDF format

- View or download the transcribed version of this page in PDF format.

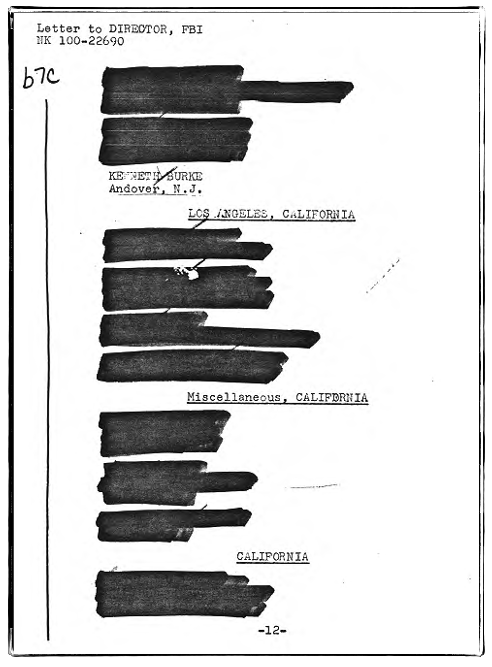

Page 13

Burke would have loved this page from the files. His is the only name not blacked out.

- View or download this single page in PDF format

- View or download the transcribed version of this page in PDF format.

Page 14

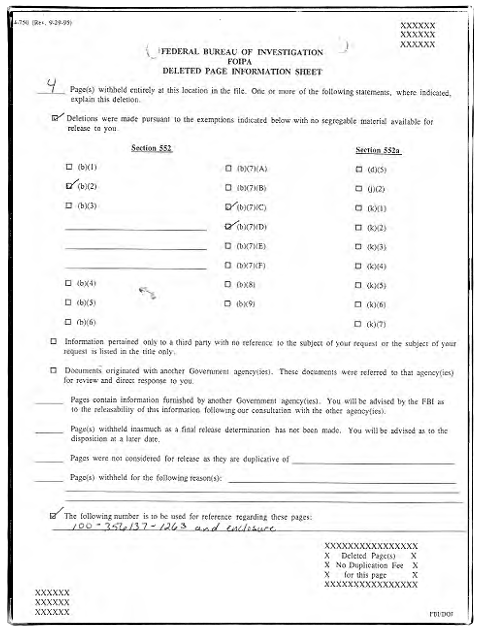

This information sheet indicates that four pages have been withheld from this location in the file. The deletions were made for reasons 552-b.2, b.7.C, and b.7.C). The numbers refer to items in the Freedom of Information Act law, which states the following:

b.7.C: "could reasonably be expected to constitute an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy."

b.7.D: "could reasonably be expected to disclose the identity of a confidential source, including a State, local, or foreign agency or authority or any private institution which furnished information on a confidential basis, and, in the case of a record or information compiled by a criminal law enforcement authority in the course of a criminal investigation or by an agency conducting a lawful national security intelligence investigation, information furnished by a confidential source."

- View or download this single page in PDF format

Page 15

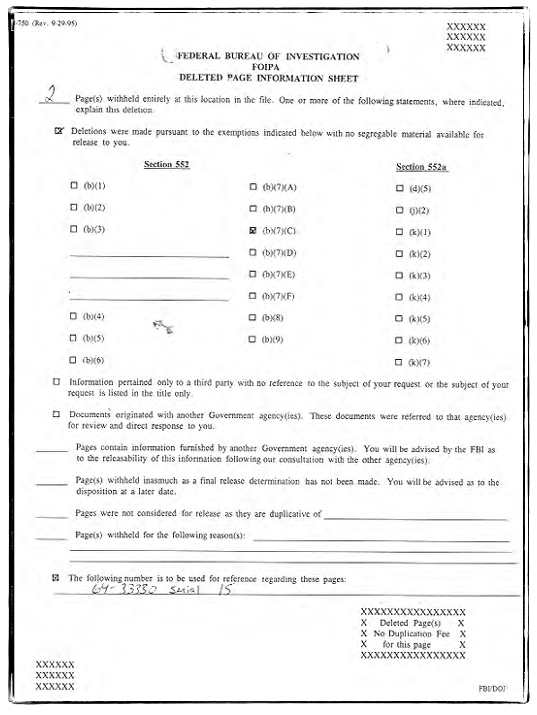

Once again, the FBI has withheld two pages from the file, on the basis that it

b.7.C: "could reasonably be expected to constitute an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy."

Interestingly, such decisions may be appealed. Burke would appreciate the simplicity of the rhetoric required (in italics):

"There is no specific form or particular language needed to file an administrative appeal. You should identify the component that denied your request and include the initial request number that the component assigned to your request and the date of the component's action. If no request number has been assigned, then you should enclose a copy of the component's determination letter. There is no need to attach copies of released documents unless they pertain to some specific point you are raising in your administrative appeal. You should explain what specific action by the component that you are appealing, but you need not explain the reason for your disagreement with the component's action unless your explanation will assist the appeal decision-maker in reaching a decision. " (From the The Department of Justice Freedom of Information Act Reference Guide )

- View or download this single page in PDF format

Page 16

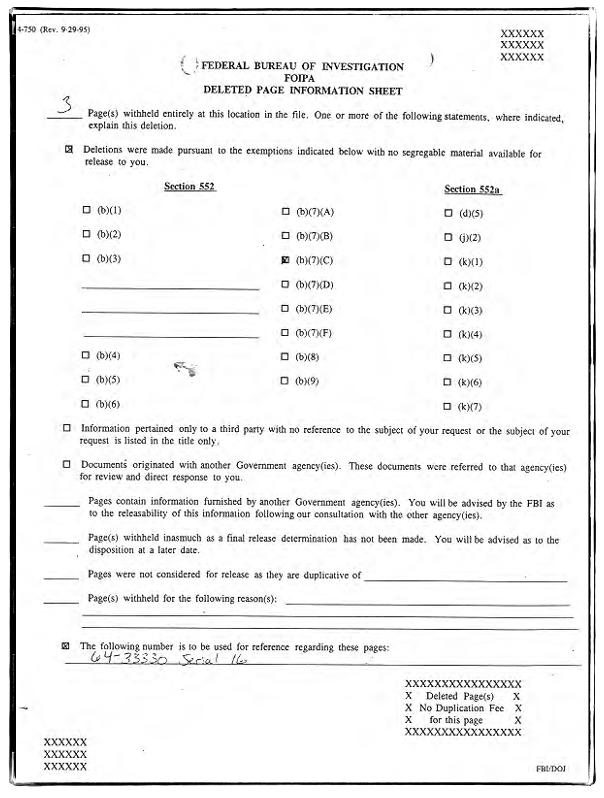

Yet again, three more pages have been withheld from this location in the file because it has been deemed that releasing the information would violate someone's right to privacy.

In sum, nine pages of material have been withheld, which is roughly one-third of the entire file, all from the period between the previous entry (1954) and the next, which is from 1956.

That period was, of course, during the height of the McCarthy frenzy in the United States, a time when hundreds of thousands of civilians were being recruited by the U.S. Air Force as plane spotters amid fear of an invasion by the "Red Menace."

Burke was during this period producing work for The Rhetoric of Religion and for his Symbolic of Motives, which he still planned to complete and that only appeared in fragments in other works, such as Language as Symbolic Action (1966), until the posthumous publication of Essays Toward a Symbolic of Motives, 1950–1955 in 2007.

- View or download this single page in PDF format

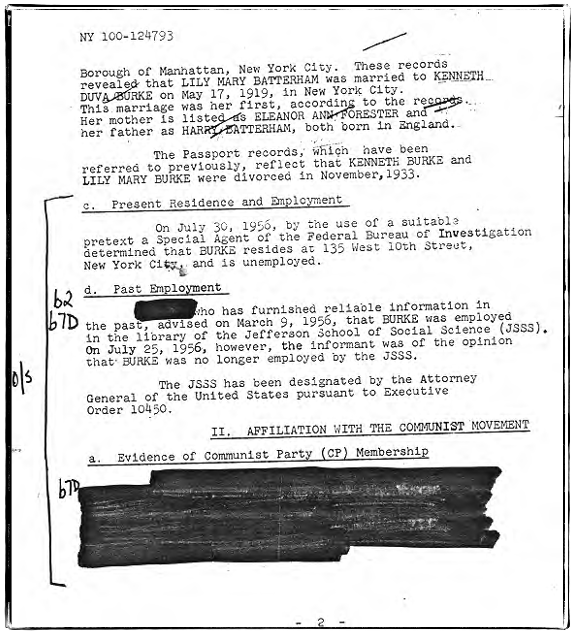

Page 17

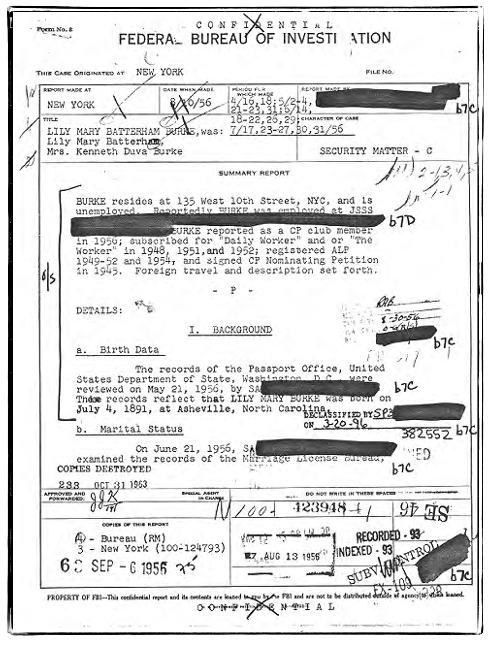

The next two documents concern Lily Batterham, who was Burke's first wife and the sister of his second wife, Libbie. According to the record, Burke and Lily were officially divorced in 1933.

The FBI believes that Lily was a member of the Communist Party. Burke himself claimed that he was never a card-carrying member, and nothing in the FBI file seems to contradict that.

JSSS stands for "Jefferson School of Social Science."

- View or download this single page in PDF format

- View or download the transcribed version of this page in PDF format.

Page 18

The Jefferson School for Social Science was designated by the Attorney General as having "affiliation with the Communist movement." The evidence for that has been blacked out, and the document ends here.

- View or download this single page in PDF format

- View or download the transcribed version of this page in PDF format.

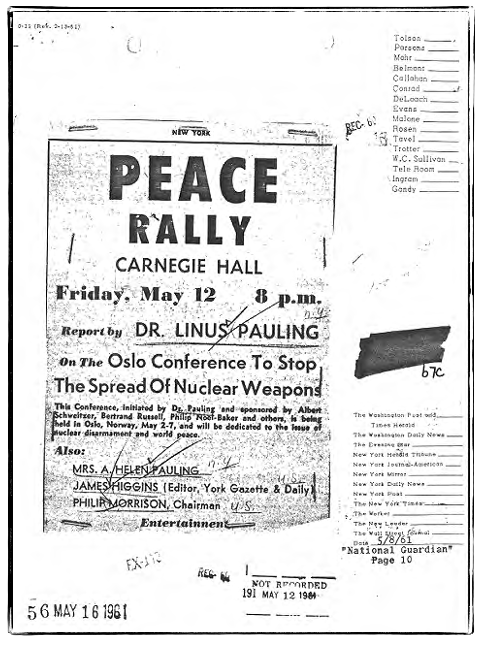

Page 19

From the late forties on, Linus Pauling, as a member of Einstein's Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, actively sought to educate people about the dangers of nuclear war. Pauling won the Presidential Medal of Merit in 1948 and the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1954. According to his Nobel biography, in the early fifties and again in the early sixties, he encountered accusations of being pro-Soviet or Communist, allegations which he categorically denied. For a few years prior to 1954, he had restrictions placed by the Department of State on his eligibility to obtain a passport.

This Peace Rally took place in 1961. In 1962, Pauling won his second Nobel Prize (the only person ever to win two) for his peace efforts. Interestingly and because of a technicality, Pauling didn't officially receive his high school diploma until 1962.

The list of sponsors of this event appears on the next page.

- View or download this single page in PDF format

- View or download the transcribed version of this page in PDF format.

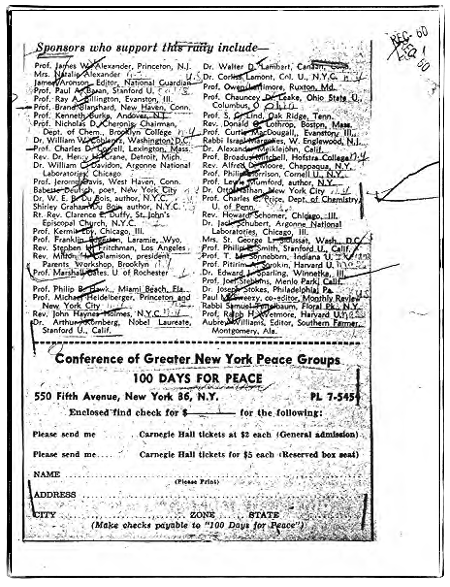

Page 20

"Prof. Kenneth Burke, Andover, N.J." is the seventh name down in the lefthand column.

Burke, of course, was deeply concerned with the dangerous machinery of war, the ultimate disease of cooperation. In a letter to William Carlos Williams on Oct. 12, 1945, just two months after atomic bombs had struck Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Burke wrote:

Meanwhile, weather permitting, I sally forth with my scythe each afternoon, to clear the weeds from the fields about the house. I have driven the wilderness back quite a bit, since the last time you were here (at least in some places, though it is patient, and ever ready to catch me napping, and move in here as soon as I go there). So, while scything, in a suffering mood, I worry about our corrupt newspapers, about nucleonics (for where there is power there is intrigue, so this new fantastic power may be expected to call forth intrigue equally fantastic), about things still to be done for the family, about a sentence that should never have been allowed to get by in such a shape. (Beineke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University).

- View or download this single page in PDF format

- View or download the transcribed version of this page in PDF format.

Credits

Todd Deam was the project coordinator who acquired Burke's FBI Files and transcribed them for publication in PDF format. David Blakesley prepared the images for web publication and wrote the running commentary. Kathy Elrick also prepared some HTML files and images.

- 23509 reads

Conflict and Communities: The Dialectic at the Heart of the Burkean Habit of Mind [Keynote Address]

James F. Klumpp, Professor Emeritus, University of Maryland

Webster's defines "keynote" as "a prevailing tone or central theme, typically one set or introduced at the start of a conference." But as you are well aware, we have already had two and a half wonderful days of our conference. "How," I was forced to ask myself, "will my voice key the notes emanating from the conference?" Perhaps, I thought, I should listen to your projects over these first two days and then hide myself away Friday night to prepare the definitive synopsis of your ideas—leading you where you wanted to go, as it were.

Now, I assume that at least one of the reasons why Nathan and Annie Laurie issued their request to me to address you is that I am one of those—shall we say "elderly sages" or "old buffaloes"?—who were fortunate enough to have spent time with the stimulus to our study, Kenneth Burke. And my thought of spending Friday evening preparing my remarks reminded me of a Burkean moment. I was fortunate enough to host KB at a conference that Jim Ford and I put together in Lincoln, Nebraska, in 1984. It was a marvelous conference on the subject of Critical Pluralism bringing together many of the great thinkers of the twentieth century including Richard McKeon, Wayne Booth, Robert L. Scott, Bruce Ehrlich, Ihad Hassan, Ellen Rooney, Stanley Fish, and of course, Kenneth Burke. The soon to be eighty-seven-year-old Burke was scheduled to present on the third morning of the conference. With no little amount of concern, I arrived early at the hotel to retrieve my charge for breakfast. I rang his room . . . , and rang, and rang. No answer. Finally, a weak voice answered. "What time is it?" "It's 8:30 KB. You are on in an hour and a half." "Oh, my gosh, I was up all night nailing that Howdy Wit," he said. I knew immediately he meant Hayden White who had spoken the day before. And, then I realized that Burke had rewritten his presentation that would take place within hours as a response to White's presentation that had riled his feathers. "I think I will skip breakfast and sleep a bit more." "You can't do that KB," I pleaded. "You need to have something to eat." Finally, he agreed to meet me for a bowl of cereal and some juice before we walked to the conference.

As the hour for his presentation arrived, he was certainly himself. The day before had ended with a presentation by Richard McKeon, who had ridden the ferry back and forth with Burke when they were studying together at Columbia University a century ago . . . in 1917 (Seltzer, 41). It was my distinct honor to host the last dinner that these two greatest humanists of the 20th century shared; McKeon would die within the year. For posterity it was at the Glass Onion in Lincoln, Nebraska. Anyway, I digress. That morning in March 1984, as Burke rose to speak, I realized that the appearance of these two displayed perfectly the contrasting habits of mind that made them so wise and so valuable to all of us working in their wake. McKeon, the day before, was as McKeon always was. He was immaculately coiffed, nattily and carefully attired in a three piece suit with a sparkling watch chain perfectly arced across his five button vest, visible through the perfect hang of his open suit coat. His wing tips were polished to a spit shine. He spoke in full sentences with each word seemingly measured. His presentation was easily outlined by those so inclined and each of his claims was presented clearly, explained precisely, and supported thoroughly.

Now this morning, the group was to hear from his counterpart in the humanistic Valhalla, Kenneth Burke. Burke's hair was in disarray. He wore a shirt that hadn't seen an iron in some time, and a green sweater lay askew around his shoulders, unbuttoned, with it quite obvious that none of those buttons were about to meet their corresponding button hole. Pants sagged just a bit. His loafers showed the mud generated from the rain the day before. As he approached the podium a sheath of yellow legal size sheets in his hand bore the unmistakable scribbles of his night's work. And sure enough, we were to hear him glide quickly from topic to topic, sometimes uttering a sentence, sometimes a fragment, sometimes a mere word, fumbling with the order of his pages, arms flailing, every once in a while breaking into that impish smile and saying "You know what I mean?" And we did. Maybe not fully grasping every thought, but certainly we understood the insightful direction he was leading us.

White sat somewhat uncomfortably, recognizing that he had been upstaged. I cannot remember the full impact of their dispute after 33 years, but I do remember the exchange that followed Burke's presentation. As I opened the floor to questions White's hand rose gingerly into the air. "It is my view that we think too little these days," White offered, "about death." Looking every year of his age, the nearly eighty-seven-year-old Burke did not pause. "Well, you may not think about it much, but I pretty much think about it all the time," he responded. The room broke into laughter and we were off to a rewarding intellectual parlor conversation.

Well, Burke would be Burke, but I decided I should not follow his example and spend a sleep-deprived Friday night preparing my remarks. For one thing, I am not as quick and witty as KB at his best, especially when sleep-deprived. But more than that, I do in fact have a message to deliver after my many years of interacting personally, and through his writings and mine, with the person who keynotes our conference far beyond my humble abilities to add or detract.

I want to make clear that I view my task today as something other than to tell you: "This is what the master actually meant." I will leave the exegesis to others. Nor am I here to declare precisely how we must now go beyond what Burke taught because the world has changed. Indeed, my pursuit is subject to neither a specific time nor a specific place. When I read Burke and similar scholarly models, I try to understand how they think through problems. "Habits of mind" is the term I used to refer to McKeon and Burke earlier: the characteristic way they array our understanding as they explain the world they experience. When we master such a habit of mind we advance our own capacity to richly encounter the experience that is life. We have not mastered an understanding, but acquired a way of seeing.

My last metaphor here has been visual which recalls one of my favorite Burkean figures: the two launches in the photograph hanging in the Museum of Modern Art. In the introduction to A Grammar of Motives, Burke described an incredibly complicated photograph: an intricate tracery of lines. But if the viewer briefly closed her eyes, opened them and looked again at the photo, she saw simplicity rather than complexity: two boats proceed side by side generating the interlocking patterns of their wakes (xvi). So, what I want to do today is to talk about what I take as a habit of mind that continually plays out in Burke's thought and journey, the simplicity of which is obscured by our seeing only the complication of his writing. Now, I will also warn you that I do not propose something made simple from cultural familiarity. No, indeed. This habit of mind has been largely lost to our culture because of our intellectual traditions and the politics of the twentieth century. Part of the reason we must seek it anew is that against our cultural and intellectual normality the habit of mind marks Burke as an aberration, not as a simple essence.

A Habit of Mind

Time to locate that habit of mind. I believe the best approach will be by triangulating the pattern, first from the perspective of our conference theme: conflict. The conference website traces the term back to its Latin roots: "to strike together." Over the years—specifically since the 1600s if we believe the OED—the term has acquired its more social meanings of combat, quarrel, or competition. I want to take my cue from the program and return to that Latin root. Two things are required for that meaning, (1) difference and (2) a vector that hurls the aspects of that difference into each other: to strike together. I think there is a word that will serve us better to communicate the imperative: "tension." I believe that Burke saw the world as composed—transitive and intransitive—through tension. Moments are given shape by the striking together. Understanding follows grasping the tensions that animate moments.

To continue the triangulation, consider a second approach: a little thought experiment. When we humans meet a moment and begin to engage it as an experience, what do we do? Many of us typically categorize: What just happened? What word best describes it? What other moment is this one like? We invoke these basic analytic tools: abstracting, naming, analogy. But I think Burke's habit of mind went at it with a slight difference. I think he experienced by seeking the tension that drew the moment into focus. What "striking together" compels us into the moment? Does it confront our expectations? Does its release of energy invite or threaten us? Are we called to become involved in resolution? What inherent conflict—what inherent energy—drew us into the moment?

Burke envisions this moment most explicitly in the beginning paragraphs of Attitudes Toward History. His living human critic—remember all living things are critics (P & C, 5)—embraces the tension of her moment. She senses the tension—the friendly and unfriendly—and having now constructed experience, begins to work into it, through the offices of human symbolic acts (ATH, 3-4).

The third perspective of our triangulation may finally put a recognizable name on this habit of mind for you: a focus on Burkean dialectic. Dialectical terms are everywhere in Burke's thinking and writing: permanence and change, identity and identification, actus and stasis, merger and division, the list goes on. These pairs emphasize how words do not define through their platonic ideal, but through their relationship with other terms. These dialectics mark tensions and they make the case for the centrality of tension. In terms of the meaning of words they reject referential theory—meaning is correspondence with a located reality—and point instead to meaning in use in context—a contextualist theory of meaning. And Burke was a major figure in the rise of contextualism in the twentieth century, perhaps its most thorough philosopher. When he considered the three orders of terms in A Rhetoric of Motives—positive, dialectical, and ultimate—it is in the dialectical order where humans live. Burke characterized this as "competing voices in a jangling relation with one another" (187). (As an aside we should note that even with the positive order of terms Burke invoked Kant to see them as "a manifold of sensations unified by a concept" (183). Thus, even a positive term is not in its essence a pointing, but a merger—a striking together.) Humans live in a web of connections where things strike together. Like the mental trick of blinking the eyes and seeing the intricate tracery turn into simplicity, encountering through abstracting, naming, and analogy disappears into a different habit of mind: dialectical tension.

This latter way into dialectic, however, emphasizes the role of words—of language, of symbolic action. After all, Burke's most concise definition of dialectic, that in A Grammar of Motives, proclaims, "By DIALECTICS in the most general sense we mean the employment of the possibilities of linguistic transformation" (402). Elsewhere, I have argued that Burke's dialectic differs from Hegel's philosophical dialectic and Marx's historical dialectic because it is a linguistic dialectic ("Rapprochement," 157). The symbol-using and mis-using animal differs because of the symbolic capacity. With language we project ourselves into the action of the world in conjunction with others. Our epistemological, sociological, and behavioral encounters develop within the capacity for language.

Well, dialectic can be complicated, particularly in Burke's hands. So, let me finally cut to a simplistic explanation: the simplest shorthand for understanding the habit of mind is the substitution of the "both/and" dialectic for the "either/or" binary. Either/or is the binary of mechanistic, referential habits of mind. The binary performs categorization and leads toward essences, platonic ideals, and what I call "hardening of the categories." Both/and turns the other way, emphasizing that division in the merger/division dialectic always draws back toward merger. Tension lies in their field of contestation—their striking together. So insistent am I that this is a key to Burke's thought that when my students parody me, they do so most often by simply mouthing in unison "both/and." But what their simplification leaves out is the complexity that opens up once our habit of mind turns to dialectical tension. For now, the contours of the striking together compel attention. What are the claims of the "and" in "both/and"? What narrative is set into action by the merger? And where does division defy the merger?

I see this as Burke's native habit of mind. Experience tension. Find the energy generated by the striking together. Accommodate both/and. Tease difference into the drive toward merger that inheres in every distinction. When encountering the either/or, transform it into its comparable both/and. Humanity—the human genius—lies in negotiating tension through the power of symbolic action.

Conflict and Communities

Of course, human action is at the center of this habit of mind. So, I suspect you are thinking about the both/and of our conference theme: conflict and communities. Going to that more socially focused pairing may provide an even fuller appreciation of Burke's habit of mind. Burke certainly formulated a sociology, developed by his disciples including most notably Hugh Dalziel Duncan and Joseph Gusfield, built on the constructs of other important contextualists in sociology, notably George Herbert Mead. There is no doubt of the presence of social concepts in Burke's work. He exploited the figure of the Tower of Babel linking language and diversity, and lodging the charge to humans to overcome that diversity through language. He exploited the figure of the wrangle of the barnyard. He portrayed war as the epitome of both cooperation and division, illustrating the extremity of dialectical tension and the both/and. He gave a central role in A Rhetoric of Motives to the dialectic of identity and identification that stresses how life is lived within the tension between the biologically autonomous individual and the loquacious inventor of community. The flow of life framed in those first two pages of Attitudes Toward History was a portrayal of communities managing the tensions of history through rhetorical interaction.

The key to understanding Burkean sociology is to grasp two things about his view. First, sociology is derived from the linguistic. Humans are the symbol using and misusing animal. Throughout daily life they transform the resources, the potentialities, of language to construct relations with their fellows, friendly and unfriendly. We are reminded that those two comm- words—community and communication—are intricately related to each other. One inheres in the other. The division in that conjunction "and" must be countermanded by the merger of "both/and." Conflict arises within the shared dialectical transformation of the linguistic into both rhetoric and social order. Perhaps this is a perfect moment to repeat the meaning of both/and, emphasizing the dialectic necessity of always forcing division into merger and vice versa.

The second key to Burke's sociology is this: Life is lived in the experiencing, creating, and cathartic relieving of dialectical tension. The concept of narrative, for example, arises from the interlocking of language and social action. No understanding of human interaction works well without understanding the linguistic transformation performed therein. I have argued elsewhere that this is the error of many treatments of Burke and hierarchy: separating the social hierarchy from the linguistic—seeing them as sequential causality—when instead they should be considered as dialectical performance. What is inevitable in hierarchy is simply how language inherently invokes and orders distinctions, and that inherent capacity is a linguistic resource, there to be exploited or transformed into the merger that is social order ("Burkean Social Hierarchy," 210-18).

Conflict and community are inextricably linked within the linguistic dialectic. Community naturally produces and is a product of conflict performed with the resources of human language. As conflict seems to divide, it requires and produces the cooperation from which the identity of communities emerges. This structural necessity illustrates again the power of both/and: conflict which seems to mark the divisions within a community is transformed as it performs the constructive process that reinforces the dance of community relations.

What Difference It Makes

I fear that I am guilty of multiplying a Burkean patois beyond easy assimilation, so let me move toward implications to illuminate what difference this Burkean habit of mind makes. Let me begin where my great teacher Bernie Brock always went: to contemporary politics. Obviously, those of us in the United States are now caught in a toxic political culture. Division is the order of the day, reason seems to have fled, and the line between words and violence seems quite thin. Conflict, indeed. Lamentation is heard daily, deploring the demise of civility, within a surrogate self-flagellation performed by our political intellectuals.

But if the habit of mind projects tension as natural, particularly in the human barnyard of politics, then the contemporary moment is reimagined. The best way to grasp this is to recall Burke negotiating the 1930s. As my co-keynoter Ann George and Jack Selzer have well documented, Burke was deeply involved in the intense political conflict of the 1930s. The politics of that decade were shaped by the tension between stability and anomie, the dialectic of permanence and change. Within that dialectic, democratic politics manifests permanence in consensus and change in ideological turmoil. At that time, as today, turmoil was clearly ascendant, but the yearning for the re-emergence of consensus was palpable. These were times appropriate to seeing politics as a striking together.

To complete the habit of mind, however, we must remember that Burke's dialectic invokes linguistic transformation. It is wise to ponder for a moment the perspective that gave rise to his two greatest political tracts: "The Rhetoric of Hitler's 'Battle'" and "Revolutionary Symbolism in America." They represent the both/and of another tension Burke lived, which I have characterized as "linguistic realism and social activism" ("Burkean Social Hierarchy," 218). The critic of "The Rhetoric of Hitler's 'Battle'" saw how political cultures constructed their motives from powerful symbolic resources with dramatic social consequences. He sought to divulge "what kind of 'medicine' this medicine-man has concocted" (PLF, 191). He worried out loud about the use of this medicine in America. In his deconstruction of the link between language and malignant political power lay the possibility of linguistic transformation of political motive.

In contrast, the social activist of "Revolutionary Symbolism" later described the intensity with which he approached his speech to the First American Writer's Congress: "I really wanted to get in with those guys." His message that day aimed at persuasion: the American party needed to adopt a vocabulary that would motivate Americans to their banner.

These two essays with their different approaches enact the merger of more tensions: the dialectic between identification with a political community and assertion of an individual political identity, paired with a tension between language's power to coordinate action through motive and the rhetor's power of persuasion to move others. Burke lived in a world which sought to bring these various tensions together in the service of linguistic transformation.

Would Burke deplore the state of our democracy? Sure, . . . in his comic way. For ironically, in the chest-pounding lament for our lost democracy today there is a surprising void of linguistic transformation. Today's public intellectuals seem to not only lack a Rexford Tugwell and William F. Buckley, they also lack an H. L. Mencken or Will Rogers. Where are the voices celebrating and invoking transcendent values to foster identification? Where are the narratives to envision a democratic resolution? The habit of mind that saw first the natural tension that defines democratic politics would seek to tease resolution, even within energetic critique.

Babel, however, was not just about politics. Genesis tells us that the Lord said, "Let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another's speech. So the Lord scattered them abroad from thence upon the face of all the earth" (King James Version, Genesis 11:7-8). Thus, the Judeo-Christian Bible linked language, understanding, and the diversity of communities. In the dialectic of his confounding, the Lord fashioned the challenge for humans to overcome their diversity. Today, in the conjunction of globalization and racism, that challenge is foremost. How would a habit of mind that began by seeing a striking together encounter the challenge?

In our world, the tensions of globalization versus tribalism (and its variant nationalism) manifest in the social conflicts that are terrorism and racism. Within their intense rancor, it is so hard to see the need for linguistic transformation.

But perhaps nowhere is the need for linguistic transformation more vivid. Underlying the current talk about these divisions is an understanding that language plays a role. The war on terror invokes the Manichean judgment of "evil" and prescribes "war," "killing the infidel," and "annihilation." Pejoratives such as "radicalized" and "hate speech" describe the language of the other in this Babel. Less prominently condemned is the dominant culture's voice: the symbolic aggression of cultural hegemony. Yet, to this point, the strategies that would transform the issues of cultural clash and once again invoke that powerful symbol of Christmas 1968—the image of the big blue marble rising above the moon—are wanting. Seeing the problem in these terms challenges this habit of mind to pull humans back toward identification and community.

It seems to this point I have sought the significance of this habit of mind exclusively on the conflict side of our conference theme. Hopefully the both/and that drives the two words of our theme together has not been lost as I have emphasized political and social conflict. So, let me ponder where we go if we emphasize the comm- side of the theme. And let me focus on that comm- interest in which most of us are occupied in some way or another: communication.

In our age, that focus teases out concern about the new technologies of communication. Late in life Burke saw and wrote about the dangers of technology, but I think he could not have foreseen the internet and the other new technologies of communication. If we begin with his habit of mind, however, and look through the eyes of dialectic, certain observations follow. At a rudimentary level, a habit of mind that begins in an inquiry of how tension draws moments into context compels students of language to engage the emerging concern with the economy of attention (Lanham). The difference is profound when tension is not the product but is the initiate of communication. A Burkean view on the economy of attention is ripe for work.

But at a more focused level, understanding the impact of the new communication technologies may be opened by their power to illustrate the dialectic of merger and division. The promise of the universality of the internet is to electronically remove divisive barriers that limit communication, to permit identification across geography and, with electronic translation, even across languages. Now, it seems, the people of earth have a new tool to overcome the Lord's decree at Babel. But alas, just as dialectic would promise, in the trajectory of the new technologies of communication the prospect of merger has confronted the reality of division. It turned out that easy access opened the power of the receiver over the author—Who shall I choose to hear?—and the openness multiplied rather than merged divisive voices. The dialectic tension created by the multiplied voices has been matched by a tension in the strategy of voice: the tension between identification—"We are one!"—and identity—"Because we are better than them!" So the new technologies have accelerated social conflict rather than resolved it. We can observe in the chatter within the new technologies, just as Burke observed about war, identification and identity enhancing both merger and division.

I do not foresee the linguistic transformation that will hasten the full potential of the new technology. We do remember that humans are "separated from their natural condition by instruments of their own making" (LSA, 16). But perhaps there are lessons in the two previous technological crises through which Burke navigated. In one—nuclear energy—we seem to have achieved a passing grade on our linguistic transformation of its potential to destroy us. At least until the potential is reignited by another linguistic transformation. The other technological crisis—the environment and global warming—is unfinished. Even Stephen Hawking is now joining the Helhaven essay's projection for the human race, albeit giving humans a bit longer to escape to another world (Holley). But linguistic transformations critique the struggle in motives that may yet save the planet. We shall see.

I finally want to consider the comm- side of our theme in concerns perhaps more familiar to many in this room: in the human capacity for creative strategic communication. How can those of us who study language and communication exploit the habit of mind that experiences human action within a striking together? Where is the potential in such habit of mind? Without fully documenting, let me charge that our tendency throughout the twentieth century was too often to view discourse and meaning referentially, and to generalize about its effects and the author's goals and achievements. We were failed stewards of dialectic. For many years of that century I taught and supervised others teaching argumentation. One of the hardest lessons for students in that classroom to learn was the concept of stasis—the point at issue in an argument; what the arguer was striking together. The notion that messages were expressions of an author's inner thoughts as a starting place for understanding was simply too strongly ingrained in the twentieth century mind.

So, if we do begin to see a message as capturing a tension—discourse contextualizing a moment into a striking together—several important things follow. We will see a text as both individual text and as context. We will see each of the terms of this dialectic pulling on the other: context arising from text and forcing limits on text. We will overcome the isolation of authorship as expression of identity and put the author's voice into relationship with engagement, toward identification. In the process, we must look always, through the strategies of messaging, into the motivational quality of language in a symbolic driven world. The result is to see more clearly the dynamic nature of the world and the role that the human capacity for symbolicity plays in that dynamism. We will become—with all living things—critics.

The Contextualist Way

I warned at the beginning that I would refuse two burdens in my keynote. First, I would refuse to "interpret the master's words." I renounced exegesis. By pursuing the habit of mind instead—moving beyond the words with the metaphor of two launches as guide—my challenge to you today is to approach your work from a more fundamentally altered orientation. Second, I promised to avoid the argument that in this new world Burke needed to be reinterpreted. Indeed, there is nothing time-bound in my message. The habit of mind I have emphasized is an alternative that opens up paths of response in any moment, past, present or future. My challenge is to try it on as Burke did. Use this habit of mind and see how it opens up the world differently. There are reasons why dialectical thinking has been so difficult in the twentieth century. But I do not have time to fully explore the historical barriers today. I would hasten to add, however, that I believe the case to pursue this habit of mind emerges strongly from its silencing in the past. And my thesis is that in seeing Burke's contribution to this well-established intellectual habit of mind we will advance our own understanding.

In characterizing his take on dialectic, I referred to Burke as perhaps the greatest philosopher of contextualism in the twentieth century. Let me end by returning there. As many disciplines developed through the twentieth century, contextualism as a mode of inquiry challenged the mechanistic view of the world. The terms here are Stephen Pepper's. Others have used different terms: humanism challenging science, interpretation challenging measurement, the subjective challenging the objective, and others. What contextualism championed was the role that the symbolic played in humans experiencing and participating in their world. The human assertion of text reached into the environment to construct context into meaning and ultimately into action. Burke's habit of mind developed through the century as he interacted with others to refine this way of thinking about humanity and its relationship to the material world. He elaborated the implications of the contextualist viewpoint: text gathered context and in its strategic core—what Burke referred to as the "great central moltenness" (GM, xix)—transformed meaning and coordinated action, by resolving the tensions emerging in interpretation. Words do not reflect change. Words do work; words perform change. Words—symbols—achieve linguistic transformation.

There is much potential in this spirit as we go forward. Those of us working to understand and guide humanity have not exhausted the potentialities of this habit of mind, of the Burkean dialectic. Much is promised by encountering the world with the different questions generated by this habit of mind: What tension drew us into the moment? What "striking together" compels us into this moment? Does the tension confront our expectations? Does its release of energy invite or threaten us? Are we called to become involved in its resolution? What inherent conflict—what inherent energy—drew us into the moment? And what resources that we can call upon as a symbol user and mis-user will guide us toward transforming our moment to join with our fellow symbolic using and misusing animals in inventing our tomorrows?

The text of this essay was first presented as a keynote address at the 2017 Conference of the Kenneth Burke Society on June 10, 2017.

Works Cited

Burke, Kenneth. Attitudes Toward History. 1937; Berkeley: U of California Press, 1984. Print.

—. A Grammar of Motives. 1945; Berkeley: U of California P, 1969. Print.

—. Language as Symbolic Action: Essays in Life, Literature, and Method. Berkeley: U of California P, 1966. Print.

—. Permanence and Change, 3rd ed. 1935; Berkeley: U of California P, 1983. Print.

—. Philosophy of Literary Form: Studies in Symbolic Action, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1941. Print.

—. "Revolutionary Symbolism in America" (speech, American Writer's Congress, New York, 26 April 1935). The Legacy of Kenneth Burke. Ed. Herbert W. Simons and Trevor Melia. Madison: U of Wisconsin P, 1989, pp. 267-73. Print.

—. A Rhetoric of Motives. 1950; Berkeley: U of California P, 1969. Print.

—. "Towards Helhaven: Three Stages of a Vision" Sewanee Review 79.1 (Winter 1971): 11-25. Print.

George, Ann, and Jack Seltzer. Kenneth Burke in the 1930s. Columbia: U of South Carolina Press, 2007. Print.

Holley, Peter. "Stephen Hawking Just Moved up Humanity's Deadline for Escaping Earth," Washington Post, 5 May 2017. Blog. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1895497983.

Klumpp, James F. "A Rapprochement Between Dramatism and Argumentation," Argumentation and Advocacy 29.4 (Spring 1993): 148-63. Print.

—. "Burkean Social Hierarchy and the Ironic Investment of Martin Luther King." Kenneth Burke and the 21st Century. Ed. Bernard L. Brock. Albany: SUNY P, 1999, pp. 207-42. Print.

Lanham, Richard. The Economics of Attention: Style and Substance in the Age of Information. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2006. Print.

Pepper, Stephen. World Hypotheses: A Study in Evidence. Berkeley: U of California P, 1942. Print.

Selzer, Jack. Kenneth Burke in Greenwich Village: Conversing with the Moderns, 1915-1931. Madison: U of Wisconsin P, 1996. Print.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

- 19033 reads

A Scapegoat for the Scapegoats: Investigating AIDS Patient Zero

Erin Doss, Indiana University Kokomo

Twenty-nine years after headlines proclaimed Gaetan Dugas as "Patient Zero" and "The Man Who Brought Us AIDS," Dugas's name appeared in headlines again, this time declaring Dugas was not singularly responsible for bringing HIV to the United States (Howard). A team of researchers in 2016 revisited samples collected from early AIDS patients and found that AIDS in the United States can be traced to multiple sources, including a pre-existing Caribbean outbreak. Although the study did not pinpoint the exact origin point of AIDS in the United States, it did establish that Dugas was not AIDS "Patient Zero," or even the first to demonstrate AIDS symptoms (Woroby et al.). Although Dugas's name has been cleared (32 years after his death), he will always have a significant role in stories of the AIDS epidemic. First identified as Patient Zero by Randy Shilts in his 1987 book And the Band Played On, Dugas was characterized as a beautiful, charismatic playboy who loved attention and casual sex with partners around the world. He was the center of every party he attended and had a wealth of friends and lovers. When he was diagnosed with Kaposi's sarcoma (a form of skin cancer often found in early AIDS patients), and later with AIDS, according to Shilts Dugas continued to pursue his promiscuous lifestyle, infecting hundreds of partners. Dugas's story is interspersed throughout Shilts's chronologically-organized book, a few paragraphs at a time, as relayed to Shilts by Dugas's friends and lovers. Shilts did not argue that Dugas was directly responsible for the AIDS epidemic, but, as reviewer Sandra Panem of Science suggested, this was not made clear to readers until page 439 of Shilts's 629-page book. Panem argued that "anyone knowledgeable knows that to pin a global epidemic on the actions of a single individual is absurd" (qtd. in "National" G2), yet that is exactly what happened in the fall of 1987.

Naming Dugas "Patient Zero" was not Shilts's immediate objective when writing And the Band Played On. Instead, he hoped to illuminate the role the media, the medical community, and the government played in allowing the AIDS epidemic to spread. Shilts was an openly gay reporter and, in the early 1980s, the only journalist in the United States covering AIDS with any regularity. Through his reporting, he became recognized as one of the only homosexual voices advocating for gay AIDS patients in the media. Shilts was the "only reporter in America who made AIDS his beat. … Shilts alone was able to tell when individuals and organizations were telling the truth. He knew the whole story" (Jones 6D). Shilts was at times ostracized by the homosexual community for his decision to write about gay sexual practices, sometimes in graphic detail, and to condemn gay leaders for their lack of effective action in curbing the epidemic (Sterel 13). However, he was known by those outside the community as a "gay activist" (Chase) and was credited with saving countless lives through his AIDS writing (Kinsella qtd. in Shaw, "A Critical" 7D).

When Shilts's book was published, however, the majority of related news coverage centered on Patient Zero. The idea of having a single target to blame for the AIDS epidemic grabbed media attention the way a reasoned, researched condemnation of government policy did not. The (often false) claims made about Dugas and attributed to Shilts created a myth of Patient Zero that I argue served to assuage the fear and guilt felt by both the homosexual community and the larger heterosexual society, and both further divided and in some ways created what Kenneth Burke referred to as "curative unification" (Philosophy 219) between the gay community and heterosexuals. However, I argue that by presenting the media with a scapegoat, Shilts built a narrative based on homophobia and provided society with a reason to ignore his carefully researched argument that the federal government and scientific community were responsible for the spread of AIDS. I build on current scapegoating literature by analyzing the case of a reporter who worked to resist the scapegoating of his community by providing two alternative scapegoats—one consciously and one seemingly unconsciously. I argue that ultimately Shilts failed to remove the gay community from its role as scapegoat and at the same time provided gays and heterosexuals with a common scapegoat, Patient Zero.

I first provide an explication of Burke's scapegoating process as it relates to my analysis and then further explain the situation of Patient Zero and the circumstances and rhetoric through which he became the ultimate AIDS scapegoat.

Burke and the Scapegoat

The concept of a scapegoat long outdates Burke, as the term originated in the biblical Old Testament when the Israelites were commanded to sacrifice a goat to atone for their individual and collective sin. Burke recognized the origin of the term and argued that a scapegoat could be denoted and slain symbolically through discourse. In Burke's usage, creating a scapegoat rhetorically involves three relationships between the scapegoat and society. Each of these relationships is imperative to the scapegoating process—guilt, purification, and redemption. If one aspect is missing, the scapegoating mechanism fails to function (Kuypers and Gellert). The first of these relationships is "an original state of merger," in which the scapegoat and the rest of society share the same "iniquities" in religious language, meaning the same feelings of guilt, fear, and/or uncertainty (Grammar 406). Often this guilt arises from the unavoidable hierarchies in society—as Burke noted, order is "impossible without hierarchy" (Attitudes 374). Such hierarchies are often understood in terms of good versus evil and participants must prove themselves worthy of their place in the hierarchy (Carter 9). As the moral order further builds up the hierarchy, it produces a sense of inferiority, which leads to feelings of imperfection and the need for purification. This need is intensified when those within the hierarchy are faced with the very real possibility of their impending death. The fear of death, then, in Carter's interpretation of Burke, is the "real director of the drama" (17). As a hierarchy must come to terms with its own imminent demise, those within the hierarchy begin to abuse power to compensate for their fear and uncertainty, thus creating a greater load of guilt. This guilt, then, needs to be dealt with in one of two ways according to Burke: mortification, the acceptance of guilt by society in an attempt to wash it away, or scapegoating, the process of placing the blame on someone else—the perfect vessel who both shares society's iniquities and embodies those iniquities in some way, whether tangible or through a rhetorical construction. The scapegoat is chosen because they are "worthy" of sacrifice, whether because they are seen as "an offender against legal or moral justice" who deserves punishment or are considered a candidate for "poetic justice," a vessel "'too good for this world'" (Philosophy 40).

Once chosen, Burke's vessel experiences a rhetorical "principle of division," in which the "elements shared in common are being ritualistically alienated" (1969a, p. 406). Through discourse, rhetors in some way shift society's fear, guilt, and/or uncertainty to the scapegoat, who becomes the embodied representative of society's iniquities. The scapegoat is then separated from society—rhetorically and in some cases physically. The scapegoat begins to represent "those infectious evils from which the group wants to be released" (Carter 18). As this happens, the scapegoat is forced out of society's discourse, taking with them the iniquities of society. As the scapegoat takes on the societal guilt, those remaining experience what Burke terms a "new principle of merger," in which society comes together under a new, "pure identity" created in "dialectical opposition" to the sacrifice (Grammar 406). Through this process society is saved by the alienation of the scapegoat, as "antithesis helps reinforce unification by scapegoat" (Language 19).

Although those viewing the situation from the outside may question the creation of a scapegoat, Burke posits that individuals within the situation feel a sense of catharsis as the blame is shifted and society is saved and brought together through the process of victimage. Burke clarifies that he is not saying scapegoating should bring feelings of catharsis and seem normal or natural, but that within literature, history, and rhetoric, this seems to be the result experienced by those within the situation (Permanence 16).

At the center of the scapegoating process is language. Burke argued that language is not neutral, but is "loaded with judgements," making speech an "intensely moral" act that gives hearers social cues about how to act toward objects and individuals (i.e., treating them as desirable or undesirable). Language, then, is a "system of attitudes, of implicit exhortations" (Permanence 177). For Burke, the way a person is referred to in conversation outlines a course of action toward that person. By considering the implications of discourse beyond the conversation or written text, Burke argued that language shapes reality and facilitates action—how a person is spoken about results in actions taken toward that person ("Dramatism" 92). As noted by Carter, seemingly neutral identifiers are "ethically charged," implying "All ought to be this, and none that" (7). Such language is "intensely moral," suggesting that words can be judged according to the actions they suggest, whether morally right or wrong (Permanence 177). In the case of Patient Zero, languages choices made by Shilts and other journalists ultimately impacted not just one man's legacy, but an entire community.

Scapegoating Patient Zero

To assess the usage of the term "Patient Zero" in reference to Gaetan Dugas, I chose to analyze both Randy Shilts's book And the Band Played On, published in 1987, and related media coverage. I collected 87 articles published between 1985 and 1990 which included the key words, "Patient Zero," "Gaetan Dugas," "Randy Shilts," or "AIDS." The majority of these articles appeared in 1987 (37) and 1988 (23), with all but one of the remaining articles published in 1989 or 1990. Much of the 1987-1988 coverage was directly related to the publication of Shilts's book and the controversy surrounding Patient Zero. Later articles focus on film and television treatments of AIDS stories, including the movie adaptation of Shilts's book.

I adopted a critical rhetoric approach, gathering these fragments of discourse together in a way that provides an understanding of how terms such as "Patient Zero" circulated during this period and ways these texts operate to both create and reinforce power structures (see McGee; McKerrow). In using critical rhetoric as a methodological orientation, I move from a study of public address to a study of the "discourse which addresses publics," taking on the role of an "inventor" who observes the social scene and analyzes communication fragments as "mediated" by popular culture and society (McKerrow 101). To provide a broader understanding of the discourse surrounding Patient Zero my analysis addresses the content of both the book and related media coverage. I first analyze Shilts's attempt to resist the media's scapegoating of homosexuals even as he seemingly unintentionally created the ultimate scapegoat. I then discuss the treatment of Shilts's scapegoat in the media and the ultimate impact of Gaetan Dugas's transformation into "the man who brought us AIDS" (Howard).

Shilts: Creating a Scapegoat

And the Band Played On details the spread of AIDS from its first known contact with the West in 1976 through 1985 and the announcement that Rock Hudson was dying from AIDS. Throughout his book Shilts sought to resist the labeling of AIDS as a gay problem. His introduction argued, "The story of these first five years of AIDS in America is a drama of national failure, played out against a backdrop of needless death" (xxii). Shilts continually placed the blame for AIDS on the Reagan administration's refusal to fund AIDS research, the scientific community's focus on competition and career advancement, public health and local government officials for failing to act, and gay leaders for playing politics instead of working to preserve lives. From a dramatistic perspective, Shilts attempted to change the public narrative of gay men as responsible for AIDS, instead describing a situation in which victims were given incomplete or false information and were allowed to act in unsafe sexual practices that led to contracting AIDS. He described the bathhouses, locations where gay men could have sexual encounters with multiple partners each night, in graphic detail and chronicled the minimal efforts made to shut them down. His description of the scenes allowed to exist in New York, San Francisco, and elsewhere demonstrated that gay men found themselves in a situation custom made for the spread of disease with no government, health, or community leaders willing to intervene.

As Shilts made the case that the government and societal hierarchy was to blame for the rise of AIDS, he also made it clear that AIDS was being overlooked and underfunded because it only affected homosexuals. Part of this blame lay with the lack of media coverage related to AIDS. For example, the New York Times did not run a story about AIDS on the front page until 1983 when the United States had already seen 1,450 cases of AIDS and 558 AIDS deaths, and the Los Angeles Times ran its first lead AIDS story in 1982 with the headline, "Epidemic affecting gays now found in heterosexuals" (Clare, 1988). As Shilts put it, the lack of media coverage about AIDS and the slow response of the medical community and the Reagan administration was "about sex, and it was about homosexuals. Taken together, it had simply embarrassed people—the politicians, the reporters, the scientists. AIDS had embarrassed everyone… and tens of thousands of Americans would die because of that" (And the Band 582). Shilts understood that homosexuals were becoming the scapegoats for AIDS. The language used in media stories related to AIDS demonstrate Shilts's concern about the scapegoating of AIDS victims and their position within the social hierarchy. As more AIDS victims died and threatened to bring the gay community into the forefront of conversation, the media continually refused to write about gay AIDS victims. As Carswell noted, newspapers "sought stories about 'real' people—that is, not homosexuals, bisexuals, drug users and others who were the early unwilling victims of the HIV virus" (4). Shaw also supported this assessment of the media's attitude toward AIDS, writing that "the American media didn't cover AIDS in any meaningful way until it seemed to threaten 'normal' (i.e. heterosexual) men and women and their children" ("A Critical" 7D).

While phrases in media coverage such as "real people," "normal," and "gay plague" clearly separated homosexuals from the heterosexual population, Shilts presented gay leaders as "real" people in their own right. The majority of his book deals with the men and women trying to fight the spread of AIDS. Shilts chronicled the few successes and many setbacks in AIDS research and the attempts to raise awareness of AIDS through the eyes of these men and women. He presented each of them as a person attempting to make a difference against a seemingly unbeatable foe. Instead of framing homosexuals as the scapegoats responsible for AIDS, Shilts described them as victims caught in a horrible situation and looking for help. By switching the focus from gay men as the agents to gay men as the victims of the scene, Shilts resisted the scapegoating of homosexuals and provided an alternate scapegoat—the federal government and scientific community, both of which he argued had failed to deal with AIDS in any real way. As noted by Foy, scapegoats rarely have the opportunity to resist the scapegoating process, as their voices are usually silenced (105). Shilts, however, refused to be silenced and used his position as a journalist to argue that homosexuals were the victims of AIDS rather than its perpetrators.

While Shilts's motive in writing the book seems clear—resisting the public's view of AIDS as a gay problem and focusing instead on the need for research and funding—he also included the perplexing story of Patient Zero, Gaetan Dugas. In a book about victims and heroes struggling to fight death, Dugas enters in the shadows of the story, making his first appearance on page 11 and quickly becoming the villain of Shilts's contradictory narrative. Even as Shilts described in detail the failings of the government and scientific community, his treatment of Dugas played on the homophobia of the broader society and provided a single, tangible evil to blame for AIDS. Dugas is first referred to as "Patient Zero" on page 23 when Shilts wrote about Dugas's "unique role" in the epidemic, one which included intentionally spreading AIDS (198). In a reversal from his strategy of focusing on scene over agent, Shilts painted Dugas as an evil agent with the knowledge of what he was doing and the desire to spread suffering. Although Dugas's story only takes up 46 pages of Shilts's book, Patient Zero became the focus of media coverage, overshadowing Shilts's careful resistance narrative.

Newspaper headlines read "Patient Zero: The airline steward who carried a disease and a grudge" (Shilts "Patient Zero") and numerous articles referred to Dugas as "Patient Zero" (see Associated Press; Carswell; Dunlop; Lehmann-Haupt; "MDs Doubt Claim,"; O'Neill). While a few articles described Shilts's reporting of Dugas's behavior accurately, most chose to focus on the idea conveyed by the term "Patient Zero." Headlines in October 1987 read "Canadian blamed for bringing AIDS to US" (Bremner), "Book singles out steward as AIDS culprit" ("Book"), and "Seductive steward blamed for spread of AIDS to US" (Hill). The New York Post even ran the headline, "The man who gave us AIDS" (Howard), a conclusion that was not supported by Shilts's discussion of Dugas or by any study conducted at the time. Shilts discussed the attention given Patient Zero and the irony of media focused on the dramatic story rather than policy (Engel; Sipchen): "Here I've done 630 pages of serious AIDS policy reporting with the premise that this disaster was allowed to happen because the media only focus on the glitzy and sensational aspects of the epidemic. My book breaks, not because of the serious public policy stories, but because of the rather minor story of Patient Zero" (qtd. in Engel). As Shilts recognized, media coverage of AIDS was shaped by the social, political, and economic climate in the United States (see Hardt). Deeply entrenched homophobia had created an environment where reporters weren't interested in writing about an embarrassing disease that impacted less than 10 percent of the population ("an aberrant 10% at that"), where political and scientific careers were threatened if they gave AIDS too much attention, and where the government and other funding agencies were loath to spend money or resources to study a "gay disease" (Shaw, "Anti-gay Bias"). In this climate neither the media nor the public was ready to accept Shilts's argument that the government and scientific community allowed the unchecked spread of AIDS. Instead, the narrative that resonated with the media—and presumably the broader public—was that of Shilts's alternative scapegoat: Patient Zero.

Dugas: The Scapegoat Rotten with Perfection

The concept of identifying a "patient zero" was not original to AIDS. The goal of discerning a single person as the starting point of an epidemic can be seen in other cases, such as the treatment of "Typhoid Mary" Mallon, who was identified as a typhoid carrier and quarantined for nearly three decades (Leavitt). The actual term, however, originated in 1984 during a cluster study completed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Researchers interviewed the first 19 AIDS patients in southern California and found that four of them had sexual contact with a non-California AIDS patient, who was also a sexual partner of four New York AIDS patients. The study, which linked 40 patients in 10 cities by sexual contact, demonstrated that AIDS was an infectious disease spread through sexual contact. The study identified Dugas as "Patient 0" and included a cluster graph charting the spread of AIDS between sexual partners (Auerbach, Darrow, Jaffe, & Curran 488). The study did not identify Dugas as having brought AIDS to the United States. Instead, it demonstrated the connection between Dugas's sexual activity and AIDS diagnoses. Dugas was first referred to as Patient "O," meaning his residency was outside California. However, as the results were clustered, the abbreviation was misinterpreted and Dugas became known as Patient "0," a clear error when Dugas's file named him "Patient 057," the 57th patient whose records were sent to the CDC (Worobey et al. 4). Labeling Dugas "Patient 0," however, provided a much different implication—an instance of Burke's "impersonal terminology" (A Rhetoric 32). The danger of using impersonal terminology is that it strips away the moral implications of humanity and contributes to the "satanic order of motives"—the process in which scientific investigation, and potential bias, can lead to treating individuals as less worthy of attention and aid, and, in extreme cases, as an evil to be eradicated (A Rhetoric 32; see also Mackey-Kallis and Hahn 13)

By the time Dugas's name became synonymous with the spread of AIDS, he had already died from AIDS-related complications. In fact, Dugas died the same month he was (anonymously) identified as "Patient 0" (March 1984), and three years before Shilts narrated his activities. Any information known about Dugas came from CDC interviews, which focused on his sexual encounters (he boasted of sleeping with nearly 2,500 partners), and from Shilts's book. In his narratives about Dugas, Shilts described him as "what every man wanted from gay life" (439), the man who thought himself "the prettiest one" and wanted to "have the boys fall for him" wherever he went (21). Shilts's description of Dugas fit perfectly with the gay stereotype already associated with AIDS, making Dugas's promiscuity and lack of concern about spreading his disease seem indicative of the entire homosexual community. According to Shilts, after Dugas was diagnosed, first with Kaposi's sarcoma, and later with AIDS, he continued to visit the bathhouses and told friends he was going to keep having sex because no one had proven that AIDS was sexually transmitted. Later, in 1982, there were reports of a man who would have sex in the bathhouses, then turn up the lights to reveal his Kaposi's sarcoma lesions, saying, "I've got gay cancer. I'm going to die and so are you" (And the Band 165). In these examples and others Dugas is portrayed as vain, angry, and unwilling to take responsibility for his actions. He is described as being angry he got AIDS and feeling justified in spreading it to others. "'Somebody gave this thing to me,' he said. 'I'm not going to give up sex.'" (And the Band 138). When Shilts wrote about Dugas's death he highlighted the irony of Dugas's life, that what had made him the epitome of the perceived gay ideal was quickly destroyed by AIDS. As Shilts wrote, "At one time, Gaetan had been what every man wanted from gay life; by the time he died, he had become what every man feared" (439). Shilts's suggestion that Dugas's promiscuity and irresponsibility were the ideal of gay culture characterized both Dugas and the gay community as the immoral evil many Americans already assumed them to be. Just as Burke noted that "enslavement, confinement, or restriction" must be present as the dialectic that allows us to locate freedom (Philosophy 109), so Shilts provided the narrative of a villainous gay man for society to oppose.

The Media's Scapegoat

The scapegoating of Dugas as Patient Zero began with Rock Hudson's death in 1985. At that point it became apparent that heterosexuals might not be safe from AIDS. As stated in a USA Today editorial, "With Hudson's death, many of us are realizing that AIDS is not a 'gay plague' but everybody's problem" (qtd. in Shaw, "A Critical"). Shilts and others suggested that the threat to those outside the gay community may have been exaggerated at points to "get the government and reporters moving," resulting in increased AIDS funding by 1989 as the broader society began to worry about contracting the virus (qtd. in Neuharth). These anxieties and worries about the potential of AIDS to affect the general population created the feeling of disorder Burke described when something changes in the hierarchic order (A Rhetoric). When the disease began to receive greater coverage and invade news broadcasts and front pages of "normal" people it broke the hierarchy of safety and the heterosexual community began to see themselves as susceptible to AIDS. This feeling of susceptibility to the disease and the fear of death brought heterosexuals into the realm of identification with the gay community—something most of society was not willing to accept—the "original state of merger" in Burke's scapegoating process, where both gays and heterosexuals lived in fear of contracting AIDS. Although the homosexual and heterosexual communities did not often identify, the shared fear of death brought by AIDS served as a "special case of identification"—an identification that quickly led to division (Hartzog 527).

When Shilts narrated the story of Gaetan Dugas he seemed to be setting up the perfect scapegoat for AIDS: a stereotypical gay man whose promiscuity threatened the pieties of heterosexual society. As Burke explained, pieties are "loyalty to the sources of our being," and are formed throughout an individual's experiences, both in childhood and through more formal education (Permanence 71). When these pieties are violated or challenged by others they become more pronounced (Daas 83). For the heterosexual society of the early 1980s, religious pieties and conservative ideas of what constituted proper and improper sexual practices were dominant, what Cloud termed <family values> (283).