All Hands on Deck: A Cluster Analysis of Key Images/Terms in James Cameron’s Titanic

Richard Thames, Duquesne University

Abstract

Burke claims literature can be inductively analyzed by indexing key terms and their associations—i.e., a “cluster analysis.” This critique claims motion pictures can likewise be analyzed by indexing key images, as illustrated by indexing the recurring imagery of “hands” and associated images and story elements in James Cameron’s Titanic.

Introduction: Author’s Note and Abstract

Most of this analysis was spontaneously generated in 1997 (the spring Titanic was released) during a lecture in which I was asked for an instance of “synecdoche.” For years thereafter faculty and graduate students would goad undergrads into asking me about Titanic knowing I could go “on and on.” I began lecturing on the movie more formally when teaching rhetorical criticism, discussing Richard Coe’s analysis of Bram Stoker’s Dracula as well as William Rueckert’s of the “witch elm” in E. M. Forster’s Howards End and Kenneth Burke’s of James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Yong Man. Finally, in 2011 I gathered together what notes I had for a semiotics conference at my university. By then an annotated screenplay had been published (Titanic: James Cameron's Illustrated Screenplay), a motherload of evidence external to the film itself. I wrote the essay out by hand over the course of a day, then typed it the next. That version sat for nearly ten years on my hard drive awaiting an introduction and a conclusion that I always found reasons to avoid, sensing theoretical material might aesthetically detract from the critical case. Thus, this note and extended abstract:

In his essay “Fact, Inference, and Proof in the Analysis of Literary Criticism,” Burke argues that fiction [and, one could assume, to some degree nonfiction too] can be inductively analyzed by indexing key terms and their associations, a technique he calls “cluster analysis” by which a complex concordance is assembled to aid interpretation. This essay argues that motion pictures can likewise be analyzed by indexing key images and their associations, opening interpretation to a level of composition beyond mere montage. This claim is illustrated by an analysis of James Cameron’s Titanic, specifically an indexing of the recurring imagery of “hands” and those images and story elements with which hands are associated—the hands of time (clocks/watches), a hand of poker (chance), a helping hand, lending a hand, giving a hand (applause), the laying on of hands, laying hands on another, caressing hands, fists, handguns, (hand) axes, handcuffs, a potter’s hands, an artist’s hands, etc.

In his earlier essay, “Psychology and Form,” Burke defines form as “the creation and satisfaction of an appetite.” Using a musical analogy (thus, form devoid of content), Burke argues that if the first two notes of an arpeggio are sounded, the body cries out for their resolution in a third (thus precluding our idealizing appetite as merely metaphorical). Frustrating resolution is one means of moving plot along; and the greater the frustration, the greater the satisfaction in the end. So—Rose meets Jack. They fall in love, but their love is continually frustrated. Its eventual consummation would appear to point toward a happy ending, but disaster is to follow. With the ship’s sinking and Jack’s subsequently dying, the promise of form appears to have been broken. Then, that last, most fearful frustration (that ultimately shall befall us all) is resolved in the final scene, perhaps explaining the astonishing success of Titanic across ages and cultures, speaking as it does to something profound, something essential to bodies that learn language—the formal satisfaction of a uniquely human appetite.

My analysis involves a somewhat jumbled telling and retelling, following multiple paths of formal development that may sound for those unfamiliar with Titanic (and perhaps for those familiar with it as well) like a twelve-year-old’s rendering of a favorite movie—what film critic Pauline Kael called “an eternity.” My apologies.

Figure 1. Cameron supervises filming the finale. © 1997 Paramount Pictures & the Walt Disney Company. All rights reserved.

“Just like Romeo and Juliet”

James Cameron first pitched Titanic to Twentieth-Century Fox executives as “Romeo and Juliet on a boat” (Paula Parisi, Titanic and the Making of James Cameron 34)—“a story of tragic love set against a tragic event.” Some thought the fictional story would detract from the real events, Cameron explained in the interview accompanying his screenplay. Given the sensational history and fascinating factual characters, why waste screen time on “a sappy love story”? But Cameron thought differently. Considering a dozen other films about Titanic, most dealing only with the historical situation, “there would have been little reason for audiences to line up around the block for this version if that’s all it had to offer.” Viewing the tragedy from the vantage of young lovers about whom the audience cared would make for a different experience than watching a docudrama. Cameron believed the fictional story and the real events could “turbo-charge each other,” whereas “they would not have been as powerful” apart (Titanic xii-xiii).

The film would be driven by dramatic irony, the characters’ ignorant of what the audience knows—“death and doom are coming.” A creeping dread would inform “every moment, no matter how frivolous or innocent.” Lovers “walking round and talking endlessly about sweet nothings” would work, because “we know that possibly one of them will die and certainly that everything around them will be destroyed” (Titanic xi).

Cameron was resolved “the film had to be about first young love” (Parisi 96), teenage emotions being “the most intense you’ll ever have in life.” At sixteen or seventeen, he explained, there’s a feeling “you’re on the verge of a discovery unlike anything in the history of the world, even though most people on the planet have already passed that marker.” But when it’s happening to you, it “fills your universe.” So Rose was to be seventeen, Jack twenty (Titanic xi).

The character of Rose was a “refraction” of Beatrice Wood combined with fictional elements and “memories of Cameron’s grandmothers (one of whom was named Rose1).” Born in San Francisco in 1893 and raised in New York, Wood had rebelled against her high-society up-bringing, running away at various times starting at 17, though never freeing herself from her mother until 23. She studied painting at the Académie Julien and acting and dance at the Comédie-Française. With the onset of World War I, she reluctantly returned to New York where she acted in the French National Repertory Theatre. She met cubist painter Marcel Duchamp who introduced her to art collector, diplomat, and writer Henri-Pierre Roché who became her first lover—though she became romantically involved with Duchamp too, leading to later speculation their love triangle was the basis of Roché’s famous novel, Jules et Jim (made into the classic 1961 film of the same name by François Truffaut). Befriended by art patrons Walter and Louise Arensberg, Wood was invited to regular gatherings of artists, writers, and poets associated with the avant-garde movement, a relationship that earned her the sobriquet “Mama of Dada.” British actor and director Reginald Pole introduced her to Annie Besant of the Theosophical Society and Indian sage Jiddu Krishnamurti whom she followed to Los Angeles (where the Arensbergs had moved) when an affair with Pole ended. In her 40s she became a ceramic artist and set up shop in Ojai, remaining productive past 100. In her late 80s she became a writer. Cameron learned of her from Bill Paxton’s wife who lent him Wood’s autobiography, I Shock Myself, the model and encouragement for which was Pole’s daughter-in-law, Anais Nin, herself a famous autobiographer. “Beatrice was proof,” says Cameron, “that the attributes of Rose’s character that I thought might have been perceived as far-fetched were not. When I met her, she was charming, creative and devastatingly funny” (Titanic 7 facing).

The character of Jack was inspired by Call of the Wild author Jack London, born in 1876, also in San Francisco where he grew up in a working-class family. Required from an early age to contribute to the family’s income, he sold newspapers and toiled long shifts at a cannery. At 15, he borrowed money to buy a sloop and worked as an oyster pirate until his boat was irreparably damaged. At 17 he signed onto a sealing schooner bound for Japan. Returning home to economic depression, he took grueling jobs in a jute mill and a street-railway power plant before tramping cross country. Thirty degrading days in jail for vagrancy convinced him to get his high school and college degrees. But at 21, forced for financial reasons to drop-out of the University of California at Berkeley, London headed for the Klondike. A year later, still poor and unemployed, he determined to become a writer. Thereafter he sustained a prodigious output of novels and stories as well as serving as a journalist and war correspondent. He was married twice (at 24 and 29), cruising parts of the Pacific with his second wife, sometimes in his own schooner, the Snark. He died at 40 on his ranch, probably from an accidental overdose of morphine taken to alleviate the pain of uremia. Pointing to London, Cameron contends “there is plenty of historical precedent for a character like Jack Dawson”—people at that time “were out in the world and on their own at a much earlier age than they are now.” (Titanic 20 facing)

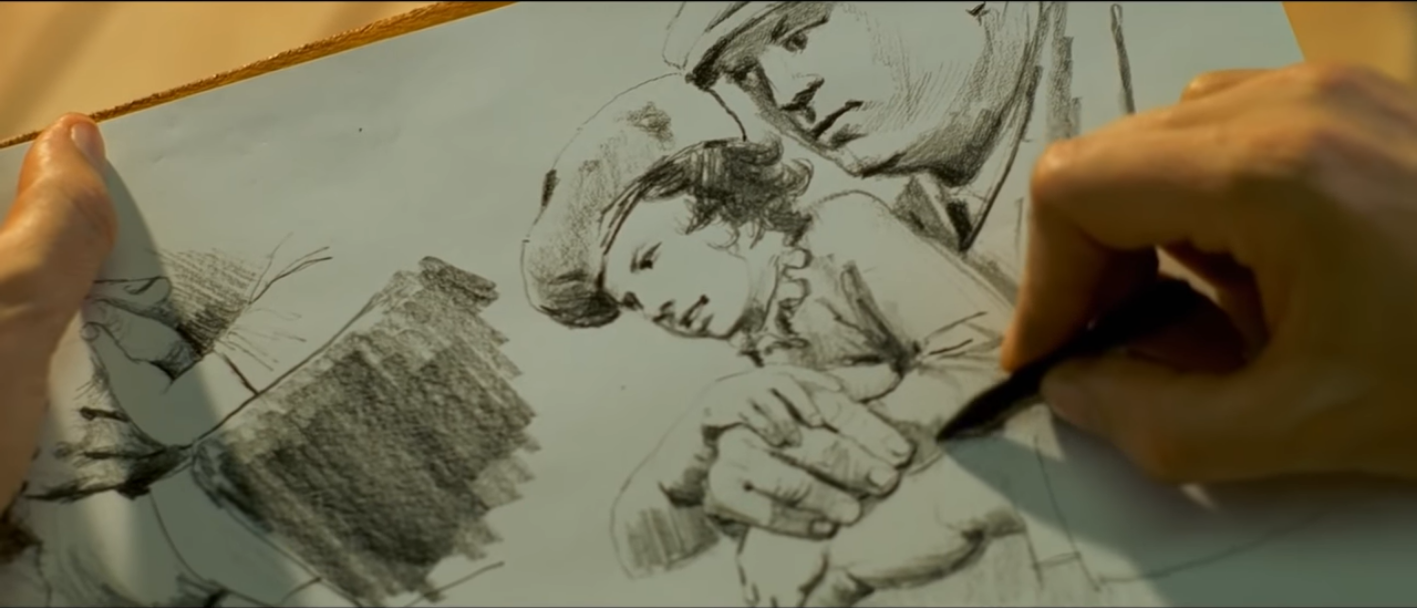

London was a self-taught writer (in fact one of the first to gain fame and fortune from his fiction alone). Cameron imagined Jack as a self-taught artist who (in a deleted scene) identifies himself with the “Ash Can” school, a realist artistic movement inspired by faces and venues of everyday life in the poorer quarters of New York (Titanic 49 facing). But Jack is Cameron too. The hands filmed in cutaway close-ups of Jack’s sketching were actually Cameron’s own (Parisi 112). (See Figures 2 and 14.)

Figure 2. Jack draws fellow passengers. © 1997 Paramount Pictures & the Walt Disney Company. All rights reserved.

Jack’s character was personal for Cameron, according to Parisi, his own personality falling “somewhere between Jack’s free-spirited artist—the person Jim wants to be—and Brock [Lovett]—the guy so focused on the logistical details, the mission [to find the ‘Heart of the Ocean’], that he’s lost sight of the big picture” (102). Paxton said he modeled Brock on Cameron, and Cameron admits that “Brock’s quest to find the diamond and my quest to make that film were very resonant” (Titanic xx).

Intriguingly, Jack tells Rose he is from Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin; Cameron himself grew up in Chippewa, Ontario, near Niagara Falls. The older Rose resides in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, only 200 miles from Chippewa Falls, suggesting Rose settles near where she and Jack might have lived had he survived.)

Where Romeo and Juliet are separated by familial enmity, clearly Jack and Rose (like London and Wood) are separated by money and class. When Jack first spots Rose (scene 56), he is sketching on the poop deck near the stern (Figure 2); she stands above at the aft rail of the B-deck promenade. His Irish acquaintance Tommy complains first-class passengers have their dogs taken to the lower decks “to shit.” So we’ll know “where we rank in the scheme of things,” jokes Jack. Then Tommy notices his staring at Rose—“You’d as like see angels fly out o’ yer arse as get next to the likes of her.” Rose and Jack represent diametrical opposites on Titanic in their likelihood of survival—first-class females having a 98% chance, third-class males 10 to 15%—“the greatest obstacle to love you can think of,” claims Cameron (Parisi 55).

In the scene (60) almost immediately following (Cameron’s having deleted most of the intervening scenes), Rose runs to the stern intent on suicide, startling Jack who is lying on a bench, staring at the stars (scene 61). Jack dissuades her, coaxing her to climb back over the rail, then saves her when she slips. In the confusion he is accused of assault—what else could be occurring with an upper-class woman screaming for help and a lower-class man lying on top of her?

But Jack is absolved and proclaimed a hero, setting in motion events that lead to his getting very close indeed; because, though separated by class, Rose and Jack are kindred spirits sharing a love of art and a longing for adventure. Randall Frakes writes in his annotation of the screenplay concerning the paintings Rose has purchased that Cameron associated the Picasso with Rose herself (who “admires his courage to try new things”) and the Monet with Jack (who “likes his visual truth”). (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3. Rose & the Picasso—note the clock. © 1997 Paramount Pictures & the Walt Disney Company. All rights reserved.

Degas’s “joyful dancers” represent “the way Rose wants to feel.” She opens her heart to Jack (scene 71, deleted in post-production) in a way she never does with Cal despite his entreaties (scene 63, see below): “There’s something in me, Jack. I feel it. I don’t know what it is, whether I should be an artist, or, I don’t know . . . a dancer. Like Isadora Duncan . . . a wild pagan spirit . . . or a moving picture actress,” which she eventually becomes (scene 21). She asks, “Why can’t I be more like you, Jack?” (scene 72). Frakes indicates the Degas is always present during Rose’s confrontations with Cal or her mother (Titanic 25 facing). Rose’s first real break with upper-class decorum comes when she joins the dancing and drinking in the third-class general room with Jack (scene 82), enraging Cal (scene 84).

Cal hardly shares Rose’s interest in art. He dismisses her prized canvases as “finger paintings” (scene 43), but grudgingly admits to liking the Degas (scene 44, deleted in post-production), perhaps indicating how he hoped Rose would feel with him—as he implies when he gives her his engagement gift, an enormous blue diamond (the “Heart of the Ocean”), saying, “There’s nothing I couldn’t give you. There’s nothing I’d deny you if you would not deny me. Open your heart to me, Rose” (scene 63). He offers his love, but at the same time offers money for her love in return, seeking to acquire her with a diamond he hopes will open her heart. She in turn would become a gem for him to own and display, an ornament for his arm. (See below—like Juliet on Paris’ arm.) When Jack joins the first-class guests at dinner as his reward for saving Rose (scene 76), the stage directions have Cal’s accepting praise from his male companions, admiring Rose like “a prize show horse.” “Hockley,” one says, “she is splendid.”

The next day after quarrelling with Ruth and Cal, Rose rebuffs Jack’s pleas to let him help—“It’s not up to you to save me” (scene 92). But shortly thereafter she changes her mind, watching a mother and her daughter at tea in the first-class lounge. As we watch the child trying so hard to please, her expression so earnest (the stage directions read), we glimpse Rose at that age and see the relentless conditioning, “the path to becoming an Edwardian geisha” (scene 93).

Ironically, despite class differences Jack and Rose face similar circumstances. Jack has never had money, but Rose has none either—as her mother Ruth reminds her daily (scene 85). Her father has left them nothing but “bad debts hidden by a good name.” As Ruth scolds her, she tightens Rose’s corset. Cameron notes Ruth’s generation was defined by the corset, while Rose’s favored a more flowing look and would have been less likely to wear one. Corseting Rose strongly underlines Ruth’s character, he continues, “and helps the audience viscerally feel how trapped Rose is” (Titanic 63 facing). Rose is tightly corseted when she runs to the stern intent on suicide, because she feels trapped by choices forced upon her by her mother’s financial circumstance. She frees herself from the corset when she has Jack draw her reclining naked on the divan. Up to that point money traps both women. Ruth dreads its loss (“working as a seamstress . . . our fine things sold at auction”); Rose dreads the means by which her mother would regain it—her own loveless marriage to Hockley.

Cal’s character was loosely modeled on Harry K. Thaw, heir to a railroad fortune, who shot and killed the famous architect Stanford White whom he suspected of having an affair with his wife, Evelyn Nesbit (as Cal suspects Jack of doing with Rose), a crime for which he spent only a few years in prison and a private asylum—men like Thaw, writes Cameron, being “almost totally insulated from the effects of their behavior by their social status and wealth” (Titanic 36 facing). Cal’s wealth may enable him to escape the consequence of his actions, but he is ensnared nonetheless, like Ruth perceiving himself and his life as worthless without money—therefore his putting ”a pistol [a handgun] in his mouth” after losses from the Stock Market Crash in 1929 (scene 283). Jack never lets his lack of money prevent his leading a rich life.

In Titanic, just as in Romeo and Juliet, an impending marriage stands as a looming obstruction to young love. Ruth admonishes Rose, the match with Hockley is a good one and will ensure their “survival”—a foreboding choice of words given what is coming.

Lady Capulet tells Juliet of her betrothal to Paris (Act 1, scene 3) the afternoon prior to a ball which Romeo and his friends attend disguised. Upon first spying Juliet, Romeo asks a servant, “What lady’s that which doth enrich the hand of yonder knight?” (Act I, Scene 5). The servant cannot say. Romeo commences a monologue, enrapt:

O, she doth teach the torches to burn bright!

It seems she hangs upon the cheek of night

As a rich jewel in an Ethiop’s ear—

Beauty too rich for use, for earth too dear.

Cameron takes up the image of the jewel from Romeo. For Rose is—like Juliet—a gem, one Cal treasures and longs to possess. Brock too treasures the gemstone worth millions. But he is disappointed to find Jack’s drawing instead in the salvaged safe (scene 15). When old Rose sees the drawing on television (scene 17), she calls Brock shipboard and teases him (scene 19)—"Have you found the ‘Heart of the Ocean,’ Mr. Lovett?” Brock asks who the woman in the picture is. Rose says she is. She’s then flown by helicopter to the research vessel. There in response to Brock’s request—“Tell us, Rose” (scene 33)—she opens her heart (scene 34 forward), described as “a deep ocean of secrets” when she concludes her tale (scene 286)—Rose, the gem, her heart, her secret all now one. Rose has carried her secret throughout her long life—a story not of tragedy but salvation, a story with the power to free Brock and his fellow treasure hunters (nay, grave robbers) and the audience as well from the grip of money. Brock confesses to Rose’s granddaughter, Lizzy (scene 288), that for three years he has thought only of Titanic but never gotten it, never let it in.

But Rose holds one last secret—the “Heart of the Ocean.” Standing on the stern rail as she had done on Titanic—in a sense standing over Jack’s grave—her story done, her heart, her secret revealed, she consigns the gemstone to the sea (scene 289).

In the original screenplay, more attention was paid to Brock’s story. He, Lizzy, and salvage crew members see Rose and dash to the stern. Realizing she’s about to cast the diamond overboard, they plead with her. Rose says she has come all this way so that the jewel “could go back to where it belongs.” Brock asks to hold the stone. She allows him, saying, “You look for treasures in the wrong place, Mr. Lovett”—thus his name [perhaps a bit too obvious]. “Only life is priceless, and making each day count.” She takes the jewel and tosses it behind her over the rail. A cascade of emotion courses through Brock who finally laughs and asks Lizzy to dance (scene 289 as filmed). But screening the entire film for the first time, Cameron realized neither he nor the audience cared at that point about Brock’s “epiphany,” giving up “his quest for material wealth in favor of the simple spiritual treasures Rose so valued” (Titanic 13 facing). Enough is said in his short conversation with Lizzy to finish his story. More would detract from the story of Rose and Jack—and the finale (Titanic xx).

Having appraised Juliet as a rich jewel, Romeo resolves [the dance or]

The measure done, I’ll watch her place of stand

And touching hers make blessed my rude hand.

Meeting Juliet, he speaks (and she responds, their dialogue comprising a sonnet),

If I profane with my unworthiest hand

This holy shrine, the gentle sin is this,

My lips two blushing pilgrims ready stand

To smooth that rough touch with a tender kiss.

Having taken up the image of a jewel, Cameron now takes up the image of hands.

Figure 4. Old Rose at the potter’s wheel. © 1997 Paramount Pictures & the Walt Disney Company. All rights reserved.

The first image of old Rose is of her hands at a potter’s wheel (Figure 4) in a home filled with memorabilia of a rich life (scene 17)—an artist now (having never let go of Jack), her hands skilled with clay like his with charcoal crayons. Likewise, the first image of young Rose is her hand as the chauffeur assists her exiting Cal‘s Renault (scene 34), and the last image the same (see Figures 1 and 18) as Jack assists her ascent of the Grand Staircase in the film’s final scene (292), ending with their kiss.

In between Cal and Jack vie for the jewel—her hand, her heart. Cal’s hands would possess her; Jack’s would caress. We know for certain she has chosen Jack when Rose breaks through the barriers of class (a lady and her chauffeur—where to? he asks; the stars, she replies), pulling him into the back of the red Renault (shown hanging from a loading crane as she steps with the chauffeur’s help onto the dock from Cal’s white one), and opens her heart, revealing, offering her inmost self—a flower, a rose, her deepest secret, a jewel of surpassing worth—a moment marked by her hand on the window wet from their breath and the heat of consummation (scenes 114 and 118). (Figure 5.)

Figure 5. Rose’s hand on the Renault’s window. © 1997 Paramount Pictures & the Walt Disney Company. All rights reserved.

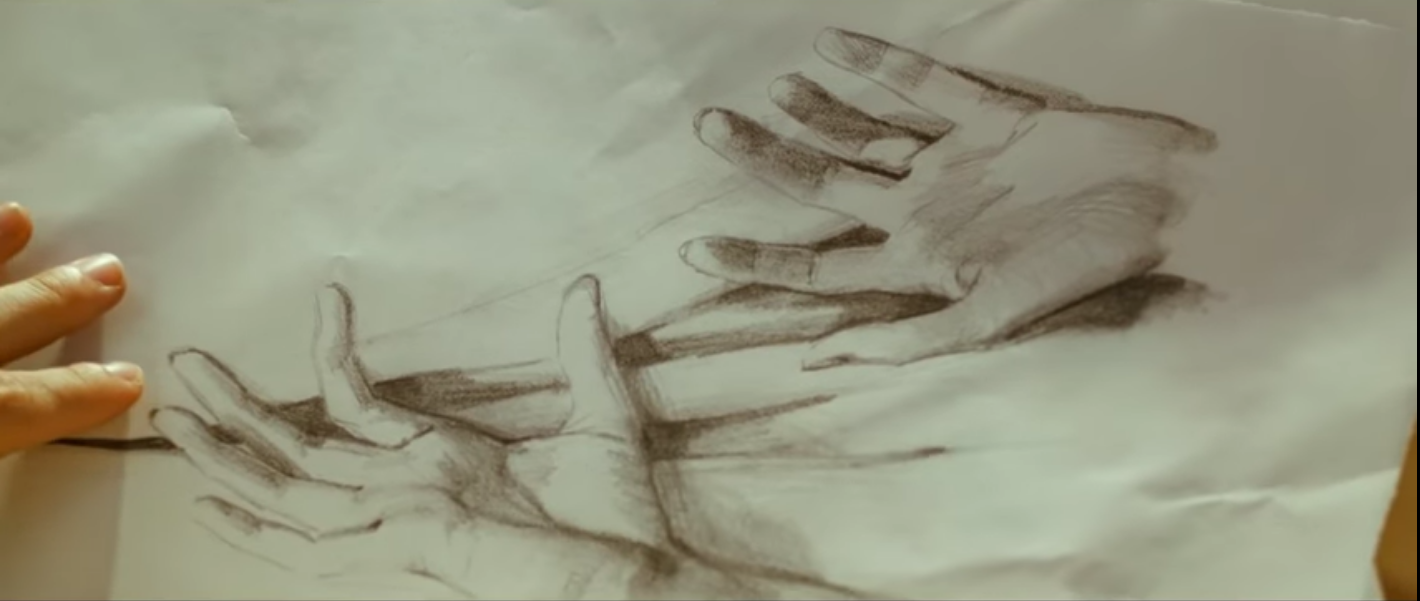

Jack, the “Ash Can” artist, is very good at drawing hands—the first thing Rose notes about his sketches (scene 69). When he sketches Rose reclining naked (move your hand just so, he says), we see his own hands in close-up (scene 100). (Figure 14.)

Figure 6. Jack’s “very lucky hand.” © 1997 Paramount Pictures & the Walt Disney Company. All rights reserved.

But the first image of Jack is of his holding a poker hand (scene 36), “a very lucky hand” (scene 78). In the pot are tickets to Titanic and a pocket-watch like the one Cal checks before boarding (scene 34), like the one ship’s architect Thomas Andrews checks for the time remaining once his ship has hit the iceberg, before adjusting the hands on a mantel clock (scene 225) after bidding farewell to Rose and Jack.

Like jewels hands mean many things—the hand we’re dealt in life, the hands of time, the hand-written note Jack hands to Rose. “Make it count. Meet me at the clock.” (scene 79)

The morning following dinner, at a worship service in the first-class dining saloon (from which Jack is barred by the stewards), we hear the hymn2 (scene 86),

Almighty Father, strong to save,

Whose arm hath bound the restless wave,

Who bidds’t the mighty ocean deep

Its own appointed limits keep.

O hear us when we cry to thee

For those in peril on the sea.

No one anticipates what the audience knows—believing like Cal that “God himself couldn’t sink this ship” (scene 34)—that they pray for themselves, that little time remains, that many in the coming night will consign themselves to the hands of God.

The ship having sunk, Jack helps Rose climb onto an intricately carved section of staircase that unfortunately can hold only one (scene 266). “I love you, Jack,” she says. He takes her hand. “Don’t say your good-byes. . . . You’re going to get out of this. . . . You’re going to die an old old lady, warm in your bed.” Then, “Winning that ticket was the best thing that ever happened to me. It brought me to you. And I’m thankful, Rose. I’m thankful.” (scene 271) He has made the most of the hand he was dealt.

He struggles to continue, “You must do me this honor. . . . Promise me you will survive. . . . Promise me now, and never let go of that promise.” She promises. He kisses her hand (the last thing he ever does in his life) just as he had earlier at the Grand Staircase. His life slips away with hers promising to follow soon thereafter. But then her eyes start open. She remembers her pledge. Gently unclasping their hands, she says, “I won’t let go. I promise.” She commits his body to the deep, then acts to save herself, to survive as she has pledged she would (scenes 274 and 276).

What does Cameron glean from Romeo and Juliet? Various plot elements—the intensity of first love, a conflict that separates the lovers (not family, but class), an impending marriage resisted by the heroine but stubbornly pursued by her mother, and a secret consummation of their love—all mentioned; while unmentioned—an older (lower-class) woman who facilitates their relationship (Nurse; Molly Brown), the hero’s commission of a crime (killing Tybalt; stealing the diamond—but see below), perhaps even the lovers joined in death. And the imagery of jewels and hands.

“One true time I’d hold to”

What does Cameron himself contribute? The final plot in all its formal eloquence. Parallels—what Cameron calls “rhyming sequences” (Titanic 136)—joining parts together in an organic whole, run throughout the screenplay and the film’s imagery, the most important being the drama of Jack’s and Rose’s first encounter at the stern (the seminal or synecdochic scene from which most of the plot emerges with all its variations [the discussion of which was the origin of this essay]) and the imagery of hands (for ultimately the cards, the timepieces, the jewel, etc.—even Rose herself!—are “handled”). Over and over, themes arise from or refer back to their meeting—obviously the theme of love, but also imprisonment and freedom, despair and hope, desperation and salvation; and overarching all the question of what we do with the time we are given—“Make it count. Meet me at the clock.” Do we love others, fully sharing the gift of life with them, or do we seek to own them, controlling life selfishly and self-righteously? Do we value others or use them as mere things?

The great “rhyming sequences” are the three at the stern (the lovers’ meeting and the ship’s sinking, with what happens at the stern contrasting with what happens at the bow; plus Rose’s casting the diamond over the stern) and the three at the staircase (the dinner’s before and after and the film’s finale; plus Cal’s contrasting gun-toting pursuit of the lovers). The stern (and bow) scenes involve themes enumerated above; the staircase scenes involve time and its value. And the two sets of scenes are held together by the imagery of hands.

Figure 7. Jack offers Rose his hand. © 1997 Paramount Pictures & the Walt Disney Company. All rights reserved.

“Take my hand,” says Jack to Rose as she stands over the vortex at the ship’s stern “like a figurehead in reverse” (scene 61). She has climbed over the rail in despair and desperation. “I felt like I was standing at a great precipice,” Rose says in her narration, “with no one to pull me back” (scene 57). But someone lends a hand.

Two days later, having sought out Jack—after watching a mother and her daughter at tea, imagining her life as an Edwardian geisha, a jewel on Cal’s arm—Rose closes her eyes and steps up on the bow rail as Jack holds her. “Do you trust me?” “Yes.”

Figure 8. Jack and Rose at the prow . . . © 1997 Paramount Pictures & the Walt Disney Company. All rights reserved.

Jack raises her arms, outstretching them like wings, then releases them, leaving a figurehead angel3 to grace the prow, transforming Titanic—no longer a ship returning her enslaved to Cal (scene 34), but a ship transporting her past Lady Liberty (who Fabrizio said he could see from the bow when the ship set out to sea—scene 54) to a life with Jack now that he has pulled her from the brink and set her free. Opening her eyes, she gasps—nothing but water around and beneath. “I’m flying!” she exclaims. Jack softly sings, “Come Josephine in my flying machine.” He raises his arms. Their hands intertwine (Figures 8 & 9). Dreaming of freedom, imagining flight—they kiss for the first time.

Figure 9. . . . their hands intertwined. © 1997 Paramount Pictures & the Walt Disney Company. All rights reserved.

But the lovers dissolve, leaving the floodlit bow of the shipwreck filling the screen (scene 96), reminding us that in six hours Titanic sinks, dashing their dreams. Jack is left in the freezing water and Rose on a floating section of staircase (imagistically tying stern and staircase scenes together), absently singing, “Come Josephine,” staring at the stars (scene 274) (where to? he asks; the stars, she replies)—just as Jack had been doing, lying on a bench, when (as luck would have it) Rose ran by (scene 61). She knows she is dying. A lifeboat’s silhouette “crosses the stars.” She turns to Jack—but finding him dead releases him to the deep, repeating her pledge to survive.

The next evening, wrapped in Cal’s topcoat (the diamond unbeknownst to her tucked in its pocket), standing in a downpour (Nature herself weeps) with steerage survivors on Carpathia’sdeck, she passes the Statue of Liberty (scene 284), with Jack’s help having freed herself of her mother and Cal and all their plans for her life. More resolute than sorrowful, inspired by the Lady’s lamp lifted against darkness and the storm, she gives her name—“Rose Dawson”—to an officer (scene 285) and, newly baptized by the rain, disembarks to lead the life she and Jack had dreamt of living.

“Take my hand,” Jack urges Rose. She tells him no, go away. “I’m involved now. If you let go, I have to jump in after you.” Her retort—“The fall alone would kill you.” Still seeking to dissuade her, Jack points out how painfully cold the water will be—foreshadowing his end. She relents and gives him her hand (foreshadowing their pledge to one another). Two days later, knowing her anguish, he pleads with Rose a second time to let him help, saying the same thing. “I’m involved now. You jump, I jump, remember?” As she had on the stern, Rose dismisses him. “It’s not up to you to save me” (scene 92). He does anyway—when she slips on the stern rail, when Titanic goes down. Rose is only on the sinking ship because she has jumped back on from the lifeboat rather than leave Jack behind—“You jump, I jump, right?” (scene 211). So, they find themselves together at the stern. “Jack, this is where we first met” (scene 246)—“one of the best moments in the film,” claims Cameron (Titanic 134 facing). They climb over the rail as the stern is lifted higher. “I’ve got you,” says Jack. “I won’t let go”—not only the exact words Jack utters when he first coaxes Rose to safety (scene 61), but the exact voice track copied “to make it the strongest possible rhyming sequence,” says Cameron (Titanic 137 facing.)

Figure 10. Jack holds on to Rose. © 1997 Paramount Pictures & the Walt Disney Company. All rights reserved.

“I’ve got you. I won’t let go,” Jack assures Rose who has lost her footing on the stern rail. She screams, suspended above the black water until he pulls her up enough for Rose to secure her footing and clamber over the rail, knocking him to the deck. They roll entangled with Jack ending slightly on top of Rose just as crewmen reach them, running to the rescue in response to her cries. Jumping to conclusions, they call for the Master at Arms who is handcuffing Jack just as Cal rushes up. “What makes you think you could put your hands on my fiancée?” he demands (scene 62). But two nights later Rose tells Jack in the backseat of the red Renault, “Put your hands on me” (scene 114). “He had such fine hands, artist’s hands, but strong too . . . roughened by work,” says Rose in a voice-over (deleted in post-production). The crewmen and Cal mistakenly assume Jack had sexually assaulted Rose, so they cuff his hands—i.e., cast the supposed criminal into “chains,” which is how she in her despair imagines herself (scene 57). Two nights later, knowing Jack has drawn Rose naked (and no doubt suspecting him of having done more), Cal falsely accuses him of stealing the diamond (scene 154) that Lovejoy had planted in his pocket (scene 153) and has him handcuffed and taken below (scene 163). Left alone in the suite, Cal slaps Rose, saying, “It is a little slut, isn’t it?” (scene 158). But later, refusing to board a lifeboat with her mother, she ripostes, “I’d rather be his whore than your wife,” and rushes off to find Jack (scene 170).

Originally Cal wrongfully assumes Jack has handled his “jewel” (which he gives to Rose in the scene [63] immediately following). But two nights later, in a sense he rightfully accuses Jack of taking the jewel he prizes (of “stealing” Rose’s “heart” or even more!)—though she was never really his. Rose saves Jack in the first instance, freeing him from handcuffs by claiming she had slipped trying to see the propellers and would have fallen overboard if not for him. And she saves him in the second instance, freeing him from handcuffs with an ax (scene 186).

The misunderstanding at the stern having been explained to the satisfaction of all (except Lovejoy who notices Jack’s boots are unlaced), Cal instructs Lovejoy to give Jack a twenty for his heroics. Reproached by Rose who asks if twenty is the going rate for saving the woman he loves, Cal invites Jack to dinner instead.

Meeting Jack the next afternoon, she thanks him for his discretion, explaining she had felt so trapped the night before, her life plunging ahead with her powerless to stop it (holding up her hand with the engagement ring to make her point). Jack advises her not to marry Cal. Rose says it’s not so simple. He asks if she loves Cal. Taking umbrage, she changes the subject, snatching his sketchbook and opening it to discover drawings which she realizes are quite good, particularly the nude with such “expressive hands.”

Figure 11. Jack’s sketch of a prostitute’s hands. © 1997 Paramount Pictures & the Walt Disney Company. All rights reserved.

(Figure 11) He shows her his sketch of “Madame Bijoux,” an old woman who sat night after night at the bar in all the jewelry she owed, “waiting for her lost love”—perhaps a particularly poignant sketch for Rose, wearing a gaudy engagement ring, remembering the immense blue stone—priceless jewelry, yes, but a life devoid of love (scene 69).

Jack tells Rose about his life—logging, sketching portraits on Santa Monica’s pier, living in Paris. “Why can’t I be more like you, Jack?” And they imagine things they might do together (scene 72)—all of which Rose eventually does, as we see from photographs the camera pans over before we first meet her (scene 17), then lingers over at the end with Rose, “an old old lady, warm in her bed,” dreaming or . . . having died (292).

That evening at dinner (scene 78—dialogue as re-written by Cameron, emphasis mine), Ruth asks Jack where he lives. The RMS Titanic, he replies. “After that I’m on God’s good humor.” And your means to travel, she asks. Working his way, he answers, tramp steamers and such. “I won my ticket on Titanic here in a lucky hand of poker . . . a very lucky hand.” Perturbed and probing deeper, she queries him concerning the appeal of “so rootless an existence.” Jack’s short speech is the heart of the film: “I figure life’s a gift and I don’t intend on wasting it. You never know what hand you’re going to be dealt next. You learn to take life as it comes at you, to make each day count.” “Well said,” from Molly. “Here, here,” from Colonel Gracie. Rose raises her glass, “To making it count.” All at the table return the toast. “To making it count.”

Figure 12. Jack slips Rose a note after dinner. © 1997 Paramount Pictures & the Walt Disney Company. All rights reserved.

Dinner over, the men excuse themselves. Jack indicates he’s heading back—to “row with the other slaves.” As he kisses her hand, he slips Rose a note—“Make it count. Meet me at the clock.” A few moments later she follows, finding him on a landing of the Grand Staircase, facing the clock (Figure 13)—the same stance he takes in the film’s finale (Figure 17), their second meeting at the clock.

Figure 13. Rose meets Jack at the clock. © 1997 Paramount Pictures & the Walt Disney Company. All rights reserved.

Rose goes with Jack to a party in steerage. Lovejoy spies on them and reports to Cal who confronts Rose the next morning at breakfast, forbidding such behavior. Rose objects and Cal becomes enraged (scene 84).

Later that morning, Ruth comes in as Rose is being corseted and forbids her seeing Jack again, insisting, “This is not a game.” They are desperate for money, her father having left them “bad debts hidden by a good name.” That name is “the only card we have to play.” Ruth is playing the hand she has been dealt, but Rose is the one in the pot (scene 85, emphases mine).

That afternoon, having been bullied by Cal and Ruth, Rose resists Jack’s entreaties to let him help. (He—“I’m involved now. You jump, I jump, remember?” She—“You don’t have to save me, Jack.”) But watching the mother and her daughter at tea, Rose changes her mind, no longer willing to live her life in “hock” to a man like Hockley. She seeks Jack out, finding him on the bow, where with his help (“Do you trust me?”) she stands on the rail like a figurehead angel, no longer in despair. She and Jack share their first kiss. They retreat to Cal’s suite, where Rose has Jack draw her wearing nothing but the diamond. She leaves the drawing and the diamond in the safe with a hand-written note—“Darling, now you can keep us both locked in your safe.”

Figure 14. Jack’s (Cameron’s) hand drawing Rose. © 1997 Paramount Pictures & the Walt Disney Company. All rights reserved.

Lovejoy enters hunting for Rose just as she and Jack exit into the corridor. They run through the engine room, eventually hiding in one of the ship’s holds and making love in the back of the red Renault. “Put your hands on me, Jack” (See Figure 5.)

Afterwards they climb to the main deck, distracting the lookouts for a critical instant, thus delaying their spotting the iceberg which Titanic disastrously grazes. Overhearing Andrews’ and the Captain’s discussion of the damage and surmising the situation’s gravity, Jack and Rose hurry to warn Ruth and Cal.

But when they reach the suite, Jack is accused of stealing the diamond which a steward finds in his coat pocket (where Lovejoy had surreptitiously planted it just moments before). Jack is handcuffed and taken below, all the while protesting his innocence. At the urging of the stewards, Cal takes Ruth and Rose to the lifeboats. But Rose refuses to abandon Jack and anxiously rushes off in search. Finding him handcuffed to a pipe on a level that is flooding, she frees him with an ax.

Trapped below with most of the steerage passengers as the water rises, they struggle to escape, finally emerging to encounter Colonel Gracie who directs them to where lifeboats are being launched. Cal arrives and with Jack’s help convinces Rose to board a lifeboat. But she leaps back onto Titanic rather than leave Jack. (“You jump, I jump, right?”) Together they race off with Cal in pursuit, firing Lovejoy’s handgun at them.

At the base of the Grand Staircase below the clock, Cal screams at the fleeing lovers as they slog through water covering the saloon, “Enjoy your time together.” Lovejoy catches up to find him laughing. “I put the diamond in my coat pocket,” says Cal, “And I put my coat . . . on her.” Resigned to losing both Rose and the gem, he turns back up the stairs to save himself (scene 212, emphasis mine).

In their flight Rose and Jack encounter Andrews who gives Rose his life-vest and wishes her luck. Once they are gone (the string quartet’s playing “Nearer my God to Thee” over the sequence of scenes that follows), he checks his pocket watch and adjusts the hands on the mantel clock to the correct time (scene 225).

Rose and Jack fight through the panicked crowd, climbing the steeply tilted deck toward the stern. They push past a man reciting the 23rd Psalm—“Yeah though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death . . . ,” with Jack chiding him to “walk faster” (scene 238 moved to the end of scene 239). Reaching the rail, Rose realizes this is where they met.

A priest’s voice carries over the din, reciting a Bible passage ofttimes read at passings:

. . . and I saw new heavens and a new earth. The former heavens and the former earth had passed away, and the sea was no longer. I also saw a new Jerusalem, the holy city, coming down out of heaven from God, beautiful as a bride prepared to meet her husband. I heard a loud voice from the throne ring out; “This is God’s dwelling among men. He shall dwell with them and they shall be his people and he shall be their God who is always with them. He shall wipe every tear from their eyes, and there shall be no more death or mourning, crying out or pain, for the former world has passed away. (Revelation 21:1-4, emphasis added)

The ship’s stern crashes back into the sea as Titanic breaks in half, only to be lifted high again, subject to the fully flooded fore section’s enormous weight. Jack scrambles over the rail and reaches for Rose. (“I’ve got you. I won’t let go.”) Swiftly filling with water, the aft section is pulled under. (“Don’t let go of my hand. We’re gonna make it, Rose. Trust me.” “I trust you,” she says, echoing her words on the prow). They jump at the last instant and struggle as the suction pulls them down. Losing hold of one another, they surface into chaos. Jack finds Rose and helps her climb onto a part of the staircase. He takes her hand and makes her promise to survive, to never let go of that promise. (“You’re going to die an old old lady, warm in your bed.”) He kisses her hand as he did at the base of the Grand Staircase before their dinner. They wait for the lifeboats. Spotting one, Rose turns but, finding Jack dead, releases him to the deep (“I won’t let go”), then fulfills her pledge—a scene suggestive of a dying Robert’s beseeching Maria to leave him in For Whom the Bell Tolls,4 “As long as there is one of us there is both of us.”

Rose concludes her story. Told they could find no record of Jack, she says there would be none. She has never spoken of him, not even to her husband. “A woman’s heart is a deep ocean of secrets,” she says. “But now you all know there was a man named Jack Dawson, and that he saved me, in every way that a person can be saved.” And then, “I don’t even have a picture of him. He exists now only in my memory” (scene 286).

That evening Rose walks alone in her nightgown to the ship’s stern and standing on its rail commits the diamond to the deep. She watches the jewel sink into “the black heart of the ocean,” glimmering “end over end into the infinite depths” (scene 289), perhaps reminiscent of Jack’s sinking “into the black water,” seeming “to fade out like a spirit returning to some immaterial plane” (scene 276).

She returns to her room. The camera lingers over pictures of the life she and Jack had talked of living—riding a horse in Santa Monica’s surf, the roller-coaster behind her; posing in front of a bi-plane (“Come Josephine . . .”). (Figure 15.)

Figure 15. “An old old woman, warm in her bed.” © 1997 Paramount Pictures & the Walt Disney Company. All rights reserved.

“One short sleep past . . . ”?

“I get asked about the ending all the time,” says Cameron:

When you love someone, you cannot imagine an end to that love, that you won’t be reunited. I think this is a basic psychological need that drives spirituality. And even though there are many people who don’t believe this, they would like to. Such a universal yearning is a powerful force to tap into. (Titanic 152 facing)

The camera pans over the last picture and then over Rose herself, “warm in her bunk. A profile shot. She is very still. She could be sleeping, or maybe something else” (scene 291). “You decide,” says Cameron (Titanic 152 facing).

But when Rose turns to Jack, the ship having sunk, the stage directions read, “He seems to be sleeping peacefully” (scene 274) like other passengers in the freezing water (scene 273)—all seemingly asleep but actually dead. Why would Rose be different, especially given Jack’s foreseeing her dying “an old old lady, warm in her bed” (scene 271).

Brock and his crew are grave robbers, the ocean a graveyard. The research vessel floats over Jack’s grave. Rose stands on the stern rail as she did when she thought to commit suicide (until Jack saved her); as she did when she feared she would die as Titanic sank (until he saved her again, making her promise to survive); as she does now, committing the diamond to the deep, a jewel of surpassing worth which has become her, her heart, her love, her life, her story, her secret revealed at last. As Rose tells Brock in the deleted scene (289), she has come all this way so that the jewel “could go back to where it belongs.” Much suggests her own symbolic burial at sea—beside Jack.

In his annotations Frakes reveals that “the script contains many references to the concepts of metamorphosis and emergence, equating Rose’s emotional transformation to that of a caterpillar [sic] becoming a butterfly” (Titanic 14 facing)—thus her ornate art-nouveau comb with a jade butterfly on the handle (scene 28) which she pulls from her hair as she disrobes (scene 99) and her silk kimono which she opens to reveal her naked body before Jack draws her reclining on the divan (scene 100). Ultimately Cameron decided to play out the butterfly theme in visuals only (Titanic 69 facing), subtly pointing toward Rose’s future metamorphosis—an emotional transformation as Frakes contends, but perhaps an ultimate one as well.

The 1892 Book of Common Prayer service for “Burial at Sea” reads,

We therefore commit her body to the deep, looking for the general Resurrection in the last day, and the life of the world to come, through our Lord Jesus Christ; at whose second coming in glorious majesty to judge the world, the sea shall give up her dead; and the corruptible bodies of those who sleep in him shall be changed, and made like unto his glorious body; according to the mighty working whereby he is able to subdue all things unto himself. (emphasis added)

We see Rose, “an old old lady, warm in her bed.” Then blackness.

Figure 16. Titanic being raised from the sea. © 1997 Paramount Pictures & the Walt Disney Company. All rights reserved.

The shipwreck looms ghostlike out of the dark. We speed along a ruined deck. Of a sudden the sea is no more and the ship transformed, returning to life. (Figure 16.)

We hear music. A steward opens a door. He ushers us before the Grand Staircase. In the gallery surrounding stand passengers and crew, all who perished with Titanic and thereafter, dressed in their finest.

Figure 17. Rose meets Jack at the clock again. © 1997 Paramount Pictures & the Walt Disney Company. All rights reserved.

A young man wearing the rough clothes of steerage stands like a groom at the altar rail, waiting where Jack first waited after dinner—facing the clock, stopped at the moment the great ship foundered—as if at the end of time. (Figure 17) Turning, Jack extends his hand, taking the hand Rose offers, ascending the staircase, resplendent in white. (Figures 1 & 18) At the landing they embrace—a lifetime past, nothing left to part them, now, again, at last, forever. The gallery applauding, he kisses the bride. (scene 292)5

Figure 18. Rose gives Jack her hand ascending the Grand Staircase (see Figure 1). © 1997 Paramount Pictures & the Walt Disney Company. All rights reserved.

Perhaps Rose dreams.

Perhaps not.

The closing prayer in the “Burial at Sea” alludes to Revelation 20:13—“And the sea gave up the dead which were in it, and they were judged, every one of them according to their deeds.”

Would Rose really dream of their meeting at the clock, Titanic’s gallery gathered entire, standing, like the host of heaven hovering, watching over her, admiring her, giving her a hand?6

You be the judge.

Credits

Originally the rights to James Cameron’s Titanic were shared by Paramount Pictures (domestic) and 20th Century Fox Film Corporation (international). In 2019 the Walt Disney Company purchased 20th Century Fox (the parent company), thereby acquiring part-ownership in the film with Paramount. Figures 2-18 are screenshots taken from the film. Figure 1 is a photo (#429 of 452) taken from the International Movie Data Base website (https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0120338/?ref_=nv_sr_srsg_0) which credits only Paramount.

Notes

1. Rose is a popular Catholic name, the flower being associated with the Virgin Mary as well as the rosary (a bouquet of prayers—“Hail Mary, full of grace . . . “).

2. An anachronism: the second and third verses from the 1937 Missionary Service Book were sung.

“Eternal Father, Strong to Save,” known to many as the “Navy Hymn,” has oft been cited as the most popular hymn for travelers in the English language. It was written in 1860 by William Whitting and has gone through numerous revisions to the present time. The hymn text was so well thought of when it was written that it was included in the 1861 edition of the highly regarded Anglican Church hymnal, Hymns Ancient and Modern, set to the “Melita” tune composed especially by John B. Dykes, one of nineteen century England’s most esteemed church musicians. The present version is taken from the 1937 edition of the Missionary Service Book, in which one of the editors, Robert Nelson Spencer, added the second and third stanzas to include a plea for God’s protection for those who travel by land and air as well as those on the high seas.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eternal_Father,_Strong_to_Save

3. Rose stands like “a figurehead angel” at the prow, but also like “Christ the Redeemer” atop Mount Corcovado watching over Rio de Janeiro like “Our Lady” watching over New York Harbor.

Suspended in a cable car to Sugarloaf our last day in Brazil, we watched the clouds obscuring Corcovado part and through the break saw the statue appear.

4. Ernest Hemingway’s great novel was made into a film starring Gary Cooper and Ingrid Bergman. Literary critic Harold Bloom argued that writers are greatly influenced by other writers. The same could be argued concerning directors and other directors. George Lucas, for example, modeled the battle for the Death Star in the first Star Wars (as well as the skirmish in the forest in the third) after a famous aerial battle sequence in the Bridges of Toko-Ri. True movie buffs could probably point to shot after shot, sequence after sequence throughout Titanic alluding to one film or another. I suspect, for example, that the finale may have been influenced by the finale of the Joseph Mankiewics’ classic (later a television series) The Ghost and Mrs. Muir. A notable quote from Captain Daniel Craig (Rex Harrison) fits Titanic—“You must make your own life amongst the living and, whether you meet fair winds or foul, find your own way to harbor in the end.” The allusion here is more a maybe than the obvious one to Hemingway.

5. The finale would have been filmed before the scenes of Titanic’s sinking. I’ve always wondered how the experience of filming the finale influenced that of filming the scenes of Titanic’s sinking afterwards and how the experience of filming the scenes of the ship’s sinking affected memories of filming the finale—a kind of mystic dislocation.

Also of note, according to the Book of Revelation time ends with a wedding. For the Victorian upper class, a meal represented gathering at the Lord’s Table, a communion that itself looked forward to the Great Communion, the wedding feast—the Messianic Banquet—at the end of time. (There was an interesting discussion of this matter in one of the short, supplemental documentaries that sometimes followed episodes of the popular public television series “Downton Abbey.”) The dinner to which Jack is invited as his reward for saving Rose from falling may itself look forward to that final feast.

I was taught in literature classes that tragedy ends in death but comedy ends in marriage and sex (sacrifice or sex recapitulating the hierogamy being the two means by which the world is ritually regenerated according to Mircea Eliade in his Myth of the Eternal Return, Princeton University Press; reprint edition, 2018). Dante of course writes The Divine Comedy and J. R. R. Tolkien claims the Gospels are the greatest fairy stories ever written (fairy stories, like comedies, being characterized by "happy" endings or eucatastrophes); they point, says Tolkien, to the Great Eucatastrope at the end of time (see his famous "On Fairy-Stories" in Essays Presented to Charles Williams edited by C. S. Lewis, Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1966).

6. The attractions of form are such that Cameron may be suggesting more than he knows. He might have meant for the end to be ambiguous. But Jack has foretold Rose’s dying “an old old woman, warm in her bed.” A priest has cited Revelation 21:1-4 (“the sea was no longer”). Dreaming of the gallery’s applauding her (“giving her a hand”) for a life well lived would not seem consistent with Rose’s character. And one might think dreaming of meeting Jack would be more intimate (reclining on the divan, lying in the back of the red Renault, standing on the bow—as an angel, no less!—a scene which would have made for a compelling ending were it not for the absence of a clock) than the spectacle on the Grand Staircase. (I dream of meeting my parents at the Table, though the table gets larger every year.) Cameron observed (quoted above), “When you love someone, you cannot imagine an end to that love, that you won’t be reunited. I think this is a basic psychological need that drives spirituality. And even though there are many people who don’t believe this, they would like to.” (Titanic 152 facing) I have argued that the expectation of form requires a resolution (at least a meeting, maybe even a marriage) at the end and that a great part of Titanic’s success is due to the immense frustration of that resolution (Jack’s death) only for that resolution to finally come, no matter how ambiguously—the greater the frustration, the greater the satisfaction. Cameron’s observation may be indicative of his own inclination (as well as that of this critic and perhaps the reader as well) concerning how that ambiguity might be resolved.

Works Cited

Burke, Kenneth. “Psychology and Form.” Counter-Statement. University of California Press, 1968, pp. 29–44.

—. “Fact, Inference, and Proof in the Analysis of Literary Criticism,” Terms for Order, edited by Stanley Edgar Hyman(with the Assistance of Barbara Karmiller), Indiana University Press, 1964, pp. 145–72.

Cameron, James, and Randall Frakes (Contributor). Titanic: James Cameron's Illustrated Screenplay, Harper Perennial, 1 January 1998.

Coe, Richard M. “It Takes Capital to Defeat Dracula: A New Rhetorical Essay.” College English, vol. 48, no. 3, 1986, pp. 231–42.

Marsh, Ed W. James Cameron's Titanic. Harper, 1997.

Parisi, Paula. Titanic and the Making of James Cameron: The Inside Story of the Three-Year Adventure That Rewrote Motion Picture History. Newmarket Press, 1999.

Rueckert, William H. Kenneth Burke and the Drama of Human Relations. 1963. 2nd ed., University of California Press, 1981.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

- 27297 reads